First there was wonder, then came the fear.

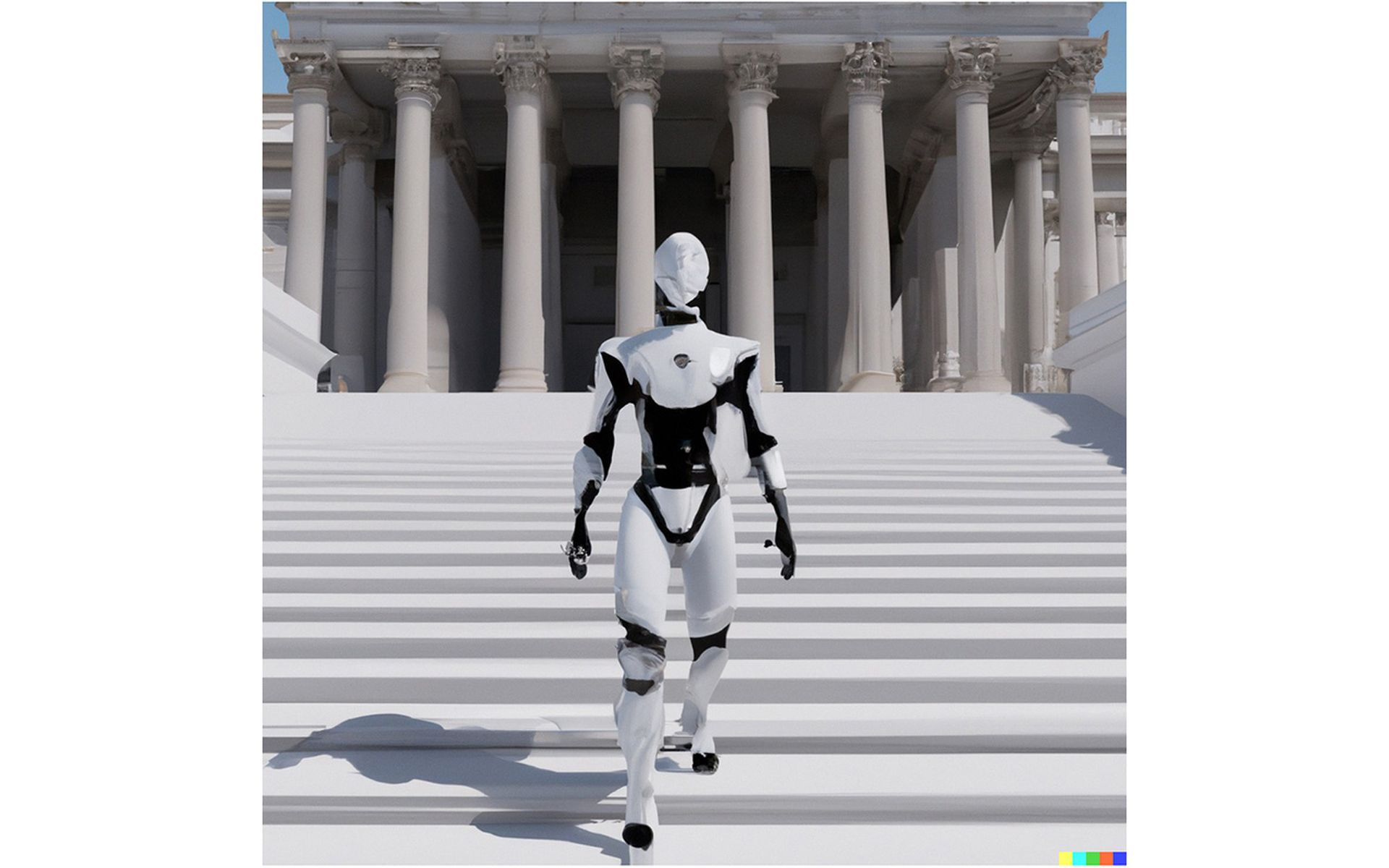

The emergence of artificial intelligence — or sophisticated large language learning models and other machine learning tools — over the past year has left policymakers scrambling to ascertain how these technologies may upend society and the global economy over the coming years.

Most of these models, while a clear leap forward in innovation, remain unready for mainstream or regular deployment or use across a broad range of industries.

They invent facts wholesale. They rely on datasets filled with other people’s work, or copyrighted or trademarked intellectual property. They are, despite the efforts of their makers, utterly amoral, as willing to give you a good recipe for making bombs as they are for a meal. OpenAI and other providers try to limit the ability of their programs to do things like this, but those protections are often relatively easy to bypass for creative prompters.

As SC Media has reported, experts in the cybersecurity world continue to grapple with the implications of advanced AI systems in their field, where tools have shown varying degrees of promise writing and detecting malicious code, crafting fluent phishing emails in other languages, conducting intrusion reconnaissance for exploiting known vulnerabilities and other offensive and defensive capabilities.

Now, tech experts and policymakers in the U.S. and abroad are giving serious thought to how best nurture artificial intelligence systems while also guarding against their worse abuses.

President Joe Biden recently warned the technology could bring enormous potential as well as “danger” to society. Bill Gates has said “we’re all scared” that AI could be used and abused by bad actors, adding that he does not believe regulators are up to the task and worries about early action kneecapping the technology’s potential over the long term. Rob Joyce, the NSA's top cybersecurity official, said the agency expects to see examples of cyberattacks that heavily incorporate ChatGPT and other tools within the next year.

While the national cyber strategy released in March doesn’t directly touch on artificial intelligence, acting National Cyber Director Kemba Walden said a number of initiatives — from developing a workforce that can compete on innovation with the rest of the world to pushing tech companies to be better stewards of data and securing or restricting semiconductor supply chains that provide the necessary compute power — would be relevant to AI as well as other technologies.

“If you break it down then it’s something that we can address, at least the cybersecurity underpinnings of AI,” Walden told SC Media and other reporters last month.

Lawmakers are starting to think about the implications as well. A bipartisan, bicameral group of legislators released a bill last month designed to ensure the influence of AI on decision-making around the use of nuclear weapons is constrained and controlled by humans.

Others worry that smaller but still serious threats, such as the use of “zero click” spyware like the Pegasus software developed by NSO Group, could be supercharged by the advanced automation provided artificial intelligence.

“What the best experts have told me is that AI is going to significantly going to bring down the cost of launching an attack like that. And then what do you do? If you train your workforce to be mindful of a phishing attack, to use [multifactor authentication] and now…none of that matters,” Rep. Eric Swalwell, D-Calif., ranking member on the House Homeland Security cyber subcommittee, told reporters last week.

Protections should address morality, bias in AI systems

This week Alexander MacGillivray, a White House advisor and deputy U.S. chief technology officer, who helps oversee and coordinate AI activities across the federal government, laid out five risk areas where the government will look to shape and possibly regulate around AI in the future.

First, AI “can increase cybersecurity threats and facilitate scams targeting seniors in online harassment,” posing safety and security concerns. They can “displace workers and inequitably concentrate economic gains,” creating disruption in the economy. AI tools are “already exacerbating bias and discrimination in many domains,” such as criminal justice, lending, housing, hiring and education, opening up a new front in the battle over civil rights. They can reveal personal information “in ways we haven’t yet experienced [and] which can further erode our privacy.” The technology can also make deepfake video, audio, images and text far more convincing, something that can “jeopardize truth, trust and democracy itself” over the long term.

Many of those principles were included in a blueprint for an “AI Bill of Rights” the administration released last year, and last month officials at four federal agencies publicly pledged to exercise all existing regulatory authorities to apply principles of fairness, nondiscrimination and safety to AI products.

That said, all of those initiatives are non-binding, and the administration has thus far relied on engagement and collaboration with industry to push common standards and protections.

Subodha Kumar, a professor of statistics, operations, and data science and director of the Center for Business Analytics and Disruptive Technologies at Temple University’s Fox School of Business, told SC Media the “first thing” regulators need to address is ensuring there are clear mechanisms for transparency into the way AI tools are built and accountability around how they’re used.

“Right now it is more like a black box model, and that is creating a lot of concerns for lots of people. And this becomes a bigger concern if users start using [these tools] more and more over time,” he said.

Those who make or integrate AI into their products should be compelled to publicly lay out the “brain behind the algorithm,” outlining to the best of their ability how their systems work and think, as well as the data they’re using to train them.

There should be direct ways to publicly vet the claims of AI companies, ensure their products are being regularly tested and lay the groundwork for fines or other regulatory actions when they fall short. Kumar suggested that an independent commission or committee set up by the government could fill such a role, and a framework proposed by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., would establish a similar independent commission to review and test AI technologies before they’re released to the public.

Additionally, last week following a meeting with tech companies, the White House announced that a number of companies will allow hackers at the upcoming DEF CON conference to test their systems for vulnerabilities and weaknesses, similar to the work the conference has done around voting systems and other technologies.

Regulation is coming. Regulation is here.

While the U.S. debate remains in its early stages, the discussion about how to put guardrails around the emerging technology has moved faster in Europe and in other parts of the world.

This week, the European Parliament overwhelmingly voted to advance legislation that would ban the use of AI algorithms in social scoring systems used in countries like China. It would also put numerous constraints around “high-risk” AI systems to ensure their decisions are managed by humans, do not lead to discriminatory actions and aren’t used for manipulative purposes.

European officials aspire for the new rules to become, in the words of Italian member Brando Benifei “a landmark legislation, not just for Europe but the world” over what they see as “life changing technology.”

U.S. lobbyists have already expressed their concerns with the Information Technology Industry Council, which counts many major tech companies as members, saying it “casts a broad brush” in placing restrictions on a wide range of AI products and technologies.

Other countries like Brazil, China and Canada have also moved to put their own rules in place.

That could put pressure on companies and policymakers to develop their own framework, but there are no signs yet of the kind of comprehensive legal solutions like the EU’s AI Act on the immediate horizon, and for many U.S. lawmakers the subject and industry is still new.

“There is a little bit of tension between promoting and allowing for innovation while simultaneously ensuring that the technology is developed and deployed in a responsible manner, and striking the right balance is something that I think a lot of lawmakers are grappling with,” one tech lobbyist told SC Media.

The slower cadence adopted by the U.S. brings both risk and opportunity. By failing to move quickly and decisively, it could continue leaving space for other countries — both friendly and hostile — to blaze a trail for U.S. companies and the rest of the world to follow.

But it could also give more time for the technology to mature and for lawmakers to work out a number of sticky issues that often dominate tech regulatory debates.

Companies will be reluctant to hand over or make public the proprietary algorithms or underlying source code and training datasets they rely on, fearing it could erode any advantage they have in what is shaping up as a burgeoning and competitive commercial AI arms race.

Additionally, large multinational corporations who develop or work on AI tools could try to influence the regulatory debate in a way that favors their products or crowds out lesser-funded entrants.

There’s wide variance in the makeup and structure of different AI tools on the market today, and Kumar said it’s probably not possible to develop a single set of rules to govern all of them. Additionally, the metrics used to cross-check and vet AI systems — by companies and regulators — will likely be “subjective,” but it could also serve as a deterrent for companies to think about how their products are explicitly designed to reduce harm.

Ultimately, he believes the societal risks in a slower approach are far greater — and real — than those that come with moving too fast to put protections in place and having to revise them later.

“The damage if we don’t take quick action the damage could be much bigger than anything we’ve seen, so I don’t see any downsides in moving too quickly…we can always relax it. I think the problem is if we move too late, that could cause problems…that would be hard to roll back,” said Kumar.