A House committee chair is worried a trio of bills meant to bolster cybersecurity operations at the Department of Energy could make it harder for the Department of Homeland Security to coordinate digital security issues across the government and energy sectors.

The Enhancing Grid Security Through Public Private Partnerships Act would direct the Energy secretary to create a voluntary cybersecurity maturity model for assessing physical and cybersecurity weaknesses in electric utilities. The Cyber Sense Act would create a separate voluntary regime to test security products and technologies that are used to support bulk power systems. Finally, the Emergency Leadership Act would require the department to empower an assistant secretary with authorities around emergencies, security, infrastructure and cybersecurity.

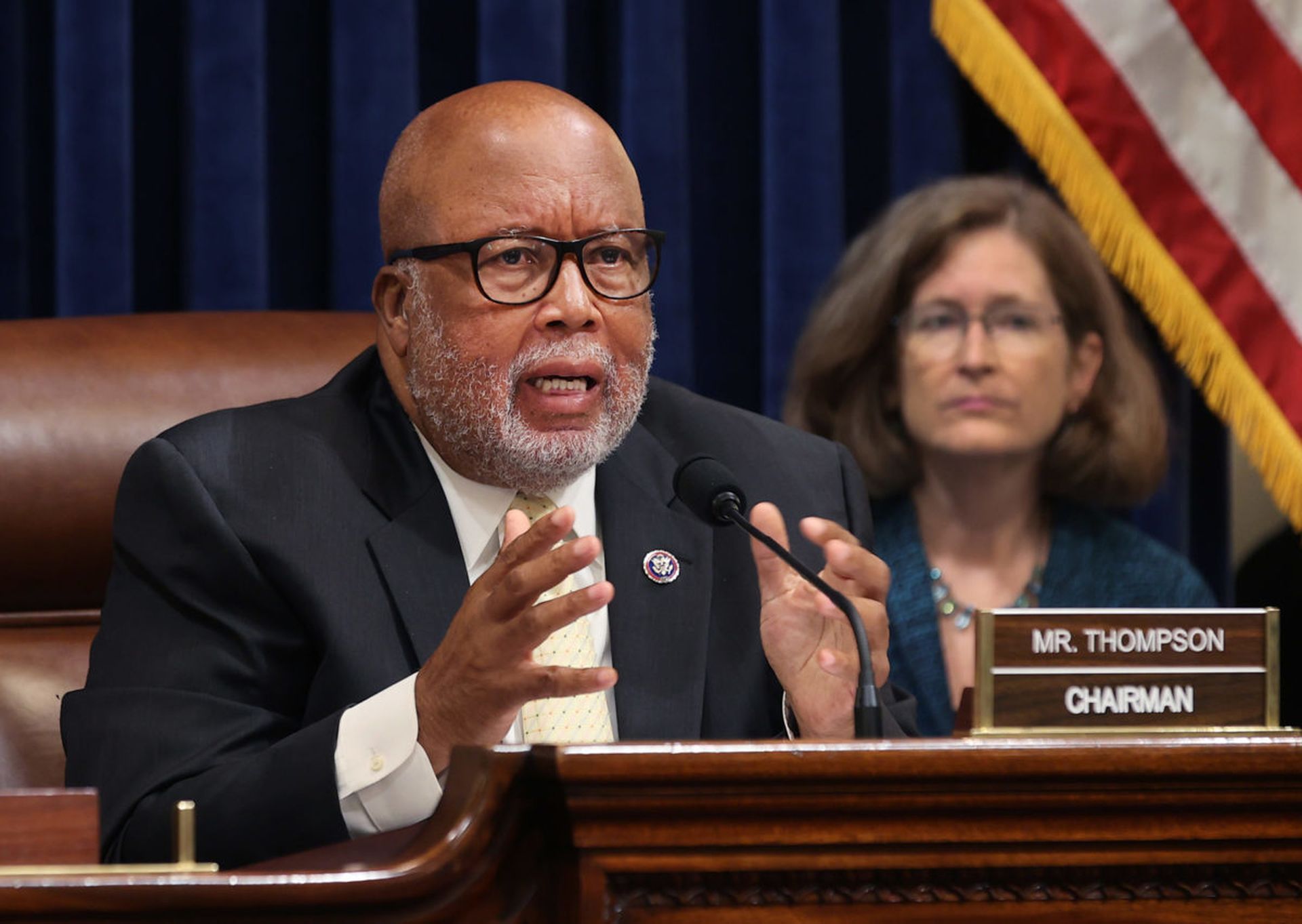

In floor comments earlier this month, Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., who chairs the House Homeland Security Committee, echoed concerns from last year that the bills as written would likely exacerbate the silos around federal cybersecurity coordination that congressional leaders have been trying to knock down for years.

“First, it runs the risk of creating a siloed, stovepiped approach to managing information about threats to the energy sector – a critically important, lifeline sector that has been under sustained attack for decades,” Thompson said. “Congress has worked to break down these siloes since 9/11, which is why DHS was tasked as a "central hub" for critical infrastructure in the first place.

"Second, having multiple federal agencies carry out overlapping roles and responsibilities creates confusion among private sector stakeholders, who are not sure who to call during a crisis, or who to partner with during steady state.”

Version of all three bills passed the House last year but died in a Republican-controlled Senate. Now, with full control of Congress and President Joe Biden in the White House, congressional Democrats in the House reintroduced the bills this year and passed them in July, with hopes of getting them through the Senate and signed into law. With recent ransomware attacks against Colonial Pipeline and JBS demonstrating broad vulnerability in the food and gas supply chains, as well as the ever present threat from state sponsored hacking groups, Congress and the White House are keen to see more cybersecurity initiatives from agencies like Energy that oversee critical infrastructure.

Thompson, who supports the underlying substance of the bills, nevertheless said that as written they could cause confusion among private sector partners by not including specific language to ensure they are coordinating their programs with DHS. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency is not only the lead civilian agency for government cybersecurity, it also often serves as the first point of contact between businesses and the government during cybersecurity incidents.

Thompson pointed to previous attacks – like the SolarWinds campaign, broad exploitation of Microsoft Exchange server vulnerabilities and a 2018 alert from DHS and FBI about a multi-stage intrusion campaign targeting multiple industries, including energy companies – that demonstrate the interconnected nature of many sophisticated state-sponsored hacks.

"Hostile foreign nations like China and Russia do not organize cyber operations one sector at a time. They wage simultaneous, parallel campaigns designed to yield the highest possible reward at the lowest possible cost," said Thompson. "It is not uncommon for attacks on the energy sector to coincide with, or foreshadow, similar attacks in other sectors."

Other congressional Democrats disagree that the bills would impair cooperation between Energy and CISA. While none of the bills specifically mention DHS or CISA, but the Cyber Sense Act and the Enhancing Grid Security Through Public Private Partnerships Act both say that the Energy Secretary will implement their programs “in coordination with relevant federal agencies." Representative Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) who chairs the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said last year that the bills do not take away any authorities from DHS and that Energy officials have committed in the past to work with CISA on cybersecurity issues in the energy sector.

Lauren Zabierek, executive director of the Cyber Project at the Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, said that may not be enough.

Congress has worked to empower CISA as the government’s premier cybersecurity agency in recent years, and efforts to communicate that to businesses and infrastructure have been a staple of the agency’s communications strategy under former Director Chris Krebs’ and current Director Jen Easterly’s tenures.

Still, Zabierek, who also served stints in the U.S. Air Force and National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, said there remains far too much jockeying in the federal government between agencies around cybersecurity and confusion in the private sector about how these authorities are dispersed and who to contact in the event of a breach. She agreed that specifically referencing the need to coordinate with CISA in the bills is a good idea, because such collaboration must often be spelled out to overcome the inertia and turf battles that define many agency cultures.

In government, “It all comes down to, honestly, the cultures and policies and whether you’re incentivized to collaborate,” she said. “You can have ‘Big P’ policies sort of up here, but if ‘Small P’ policies and incentives and cultures don’t dictate that, you don’t know what happens on the human level.”

Zabierek also pointed to another argument Thompson made in his remarks, that having too many overlapping cybersecurity responsibilities means the government will be “forced to spread an already thin supply of cybersecurity experts and resources even thinner.”

A report issued by Zabierek and her colleagues this month on improving collaboration on cyber defense issues between agencies and the private sector emphasizes similar problems around interagency cyber jurisdiction and budget limitations.

“We know that the interagency is this really tight ball of yarn basically…you add more layers and then that budget just keeps getting thinner and thinner spread across the government, nobody knows who to go to and you get these turf wars,” said Zabierek.