Researchers are claiming to have found the first-ever instance of a malvertising campaign specifically targeting WiFi-connected smart home devices.

According to a blog post from ad security company GeoEdge, the malware was spread to the IoT devices through users’ mobile devices after victims visited a website affected by a malicious ad. Certain details of the attack have not been published yet — but even so, this apparently unprecedented act could spell trouble for businesses that heavily rely on mobile and IoT devices or who allow employees to work regularly from their home networks.

Conventionally, malvertisements placed on web or mobile pages are typically designed to directly affect the device visiting the site, rerouting a user to a phishing page or triggering a drive-by download of malware. But this is altogether different.

“We are in the space for almost 10 years. We’ve never seen a malvertising campaign that actually tries to attack devices that are connected to the network,” said Amnon Siev, CEO of GeoEdge, in an interview with SC Media. “What is so unique about this specific attack is the user is actually unaware [that he/she] was exposed to the ad, and… there's not any attempt to do any [attack on] the device. It was all about scanning the local network and looking for specific vulnerabilities.”

“Using advertising platforms as the means for distribution is not a new idea, but using it to target IoT devices connected to the local area network is a new variant of an upstream attack,” agreed Dirk Schrader, global vice president of security research at New Net Technologies, now part of Netwrix.

In conjunction with partners InMobi and Verve Group, GeoEdge researchers not only uncovered the attack vector but also determined that adversaries in Slovenia and Ukraine are responsible for the campaign, which began in mid-June 2021. According to the company blog post, the attack is designed to “silently install apps on home-WiFi-connected IoT devices, and only requires that hackers possess a basic understanding of device API.”

“The code that's run on the [mobile] browser… [is] basically scanning the network in a systematic way,” for a certain device, said Siev. “And once this device has been detected, then they're leveraging a vulnerability on that device in order to install some malicious application on that device.”

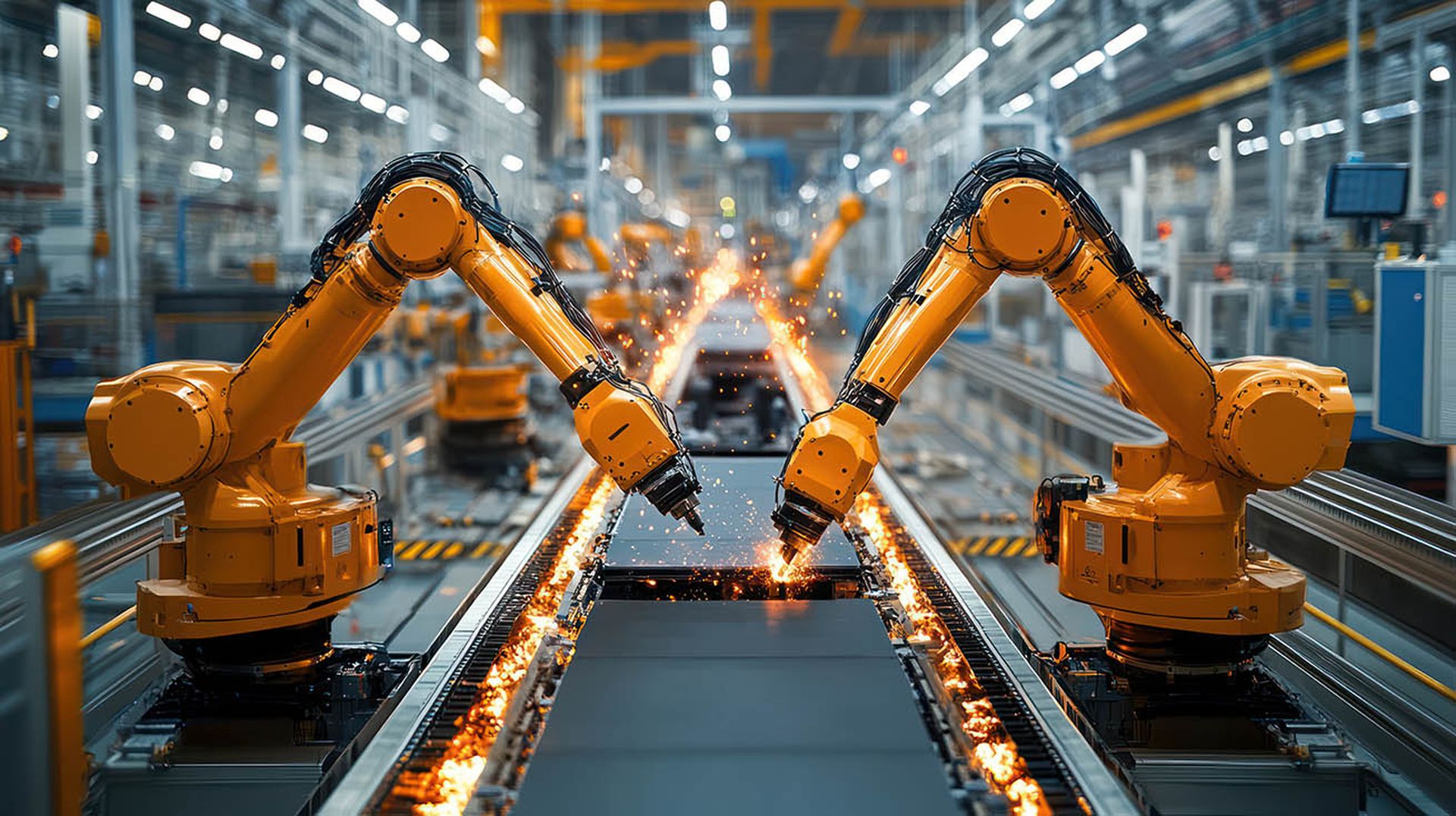

Siev at one point in the interview mentioned a “specific device” that was attacked, though he did not clarify if there were one or multiple IoT products that the attackers have been targeting. Either way, what’s important is that GeoEdge researchers confirmed that the attackers’ methodology could successfully be replicated to attack variety of IoT environments, including those found in industrial workplaces.

Indeed, Siev said that GeoEdge lab workers were able to demonstrate how a similar technique could be used to find and infect a “well-known Wi-Fi router.” Essentially, the technique involves “probing different ports” in order to locate and fingerprint a particular device. “And once you have been able to identify that specific device, you are actually performing a deeper action based on the specific vulnerability” tied to that device.

If this technique ultimately takes off amongst the cybercriminal community, businesses must prepare. After all, said Siev, an employee can easy visit a website, view a malicious ad that traditional endpoint mechanisms won’t be able to identify the attack, perhaps because they are leveraging a legit cloud infrastructure. And as is typical with malvertisements, the user doesn’t even have to interact with the ad in order for it to take effect.

Siev would not reveal the intended purpose of the attack. “My immediate concern is how these could be used to expand the scope of botnets that make use of IoT devices, such as Mirai,” said Sri Mukkamala, senior vice president of security products at Ivanti.

But that’s just one possibility. WFH employees in particular must beware, as “any infected device in the home network poses a serious risk for them,” said Schrader. “Such an established foothold allows the attackers to check the environment and to look for options to elevate their position in the networks. Whatever they do, it is likely that it will be undetected, as home networks usually don’t have that level of monitoring as a company’s infrastructure. So attackers have plenty of time to sniff, to find vulnerabilities, anything that seems useful to get closer to account information of any kind.”

Siev said that the online advertising remains a “very attractive and compelling ecosystem” for bad actors to compromise and exploit because it’s cheap to do, the ads reach a large audience, and attacks can be hard to detect and remove across a complex ad supply chain that is full of various middlemen services and third-party partners.

Chris Grove, product evangelist at Nozomi Networks, criticized the “failure of the advertising networks to secure the content they’re providing,” as well as these networks’ “questionable trust models at the web browser level.”

“How and why do advertiser networks have such trust within the browser that they can do things that we would never trust them to do?” Grove continued. “For example, asking most users if they would grant an advertising vendor access to IoT devices on their network, the answer would probably be a resounding ‘No!’ And yet, we see that malicious code loaded by advertisers is able to break out of the browsers boundaries and freely onto the local network. That seems like a failure at multiple levels, most of which are outside of the typical user’s hands.”

Simon Aldama, principal security advisor at Netenrich, said that there is a “shared responsibility between marketing agencies and operators of content delivery networks to protect end users from unknowingly being subverted through online advertisements.” While the service providers “are responsible for the detection of anomalies within the advertising delivery infrastructures, the end user “also shares responsibility for taking the risk of accessing online information without endpoint, web-browser and system protection.”

To minimize malvertising’s threat to your own networked IoT devices, “enterprises need to perform a variety of mitigations to reduce liabilities associated with the risks of working from insecure home networks,” Aldama continued. This includes “allowing conditional access to organizational infrastructures from hardened IT-issued devices, utilization of SASE [Secure Access Service Edge] access methods, updating “work from home corporate policies and procedures”, and work from home security awareness training.” Moreover, “access to sensitive information from unhygienic personal devices should never be allowed.”

Mukkamala also recommended having strong visibility into your device assets and limiting access so “you can avoid a lateral movement and limit the impact.” And Schrader suggested that companies “help their employees to set up better security in their home networks” by providing virtual desktop solutions, “or other integrated measures addressing user account monitoring, data access management, plus device hardening.”