The details of a long-awaited conclusion to a civil lawsuit may strengthen the government’s position that it can leverage a 150-year-old law to go after companies that fail to comply with cybersecurity regulations spelled out in federal contracts. However, some federal and legal experts believe the victory should be seen as partial at best, signaling that more aggressive efforts to wield the False Claims Act at scale to influence contractor behavior will likely require additional long and costly battles in court.

In May, a lawsuit against aerospace and defense vendor Aerojet Rocketdyne filed under the False Claims Act was settled two days after it went to trial. Last week, court documents revealed key details for the settlement, with the company agreeing to pay a $9 million fine, including $2.61 million to Brian Marcus, the former employee who brought the suit on behalf of the government. The civil case, first brought forward in 2015, was based primarily on allegations that the company secured billions of dollars in federal contracts from the Department of Defense and NASA while fraudulently claiming they were complying with Federal Acquisition Regulations around cybersecurity.

Kellen Dwyer, a former deputy assistant attorney general at the Department of Justice, told SC Media the case and settlement is good news for the government, one that strengthens the legal basis for using the False Claims Act to pursue contractor cybersecurity malfeasance in the future.

“I think it’s a win for the government’s side in the sense that the case made it to trial. By letting it go to trial, the judge is deciding that the theory they were bringing — that you can have an FCA claim based on insufficient compliance with cybersecurity requirements in a federal contract — is a valid theory and it's one that a court will let go forward and ultimately go to a jury,” said Dwyer, who led the government's criminal hacking cases against Wikileaks founder Julian Assange and Russian cybercriminal Aleksey Burkov as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Test for Civil War-era law to enforce cybersecurity compliance in federal contracts?

Last year, the Department of Justice announced a major initiative to rely on the False Claims Act — a law originally passed during the Civil War to deal with rampant fraud from unscrupulous contractors supplying the Union Army — to sue contractors who misrepresent their compliance with cybersecurity regulations in federal contracts.

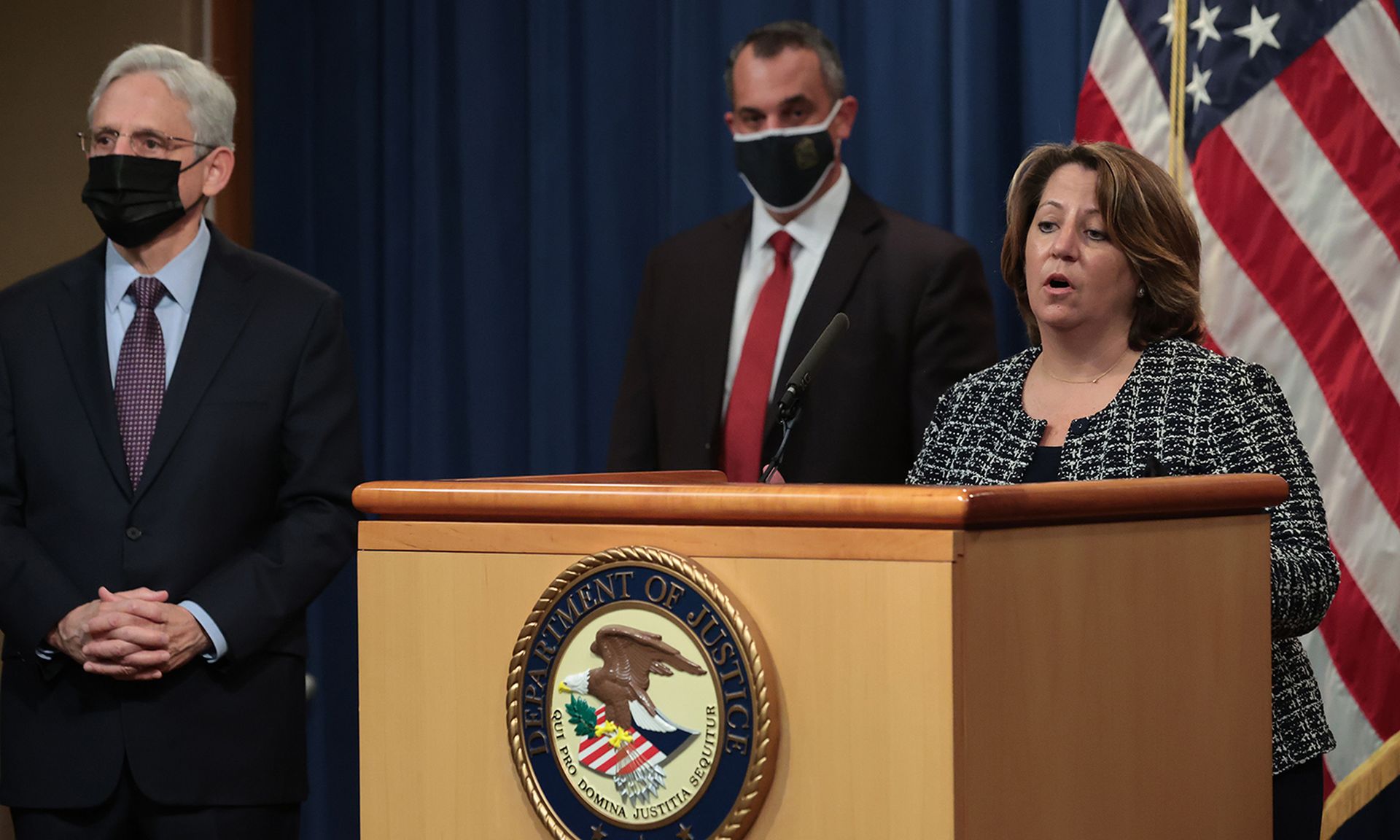

It’s a novel legal argument. While the government was not leading the suit against Aerojet Rocketdyne, it did submit a statement of interest in the case, and observers view it a test run for DoJ’s broader position on leveraging the False Claims Act. In announcing the effort last year, deputy attorney general Lisa Monaco referred to the False Claims Act the “primary civil tool to redress false claims for federal funds and property involving government programs and operations.”

“Where those who are entrusted with government dollars, who are entrusted to work on sensitive government systems, fail to follow required cybersecurity standards, we’re going to go after that behavior and extract … very hefty fines,” Monaco said.

While Dwyer said he believes the resolution ultimately strengthens the government’s argument, it’s only a partial victory because it did not result in a trial or definitive ruling in the government’s favor, and because it did not resolve “the aspirational nature of some of these cybersecurity compliance programs” and how they will be treated by courts in future cases.

Part of the defense put forward by Aerojet Rocketdyne’s lawyers when attempting to get the case thrown out was that the government has known for years that they and other contractors were not fully complying with FAR cybersecurity regulations, and yet have historically failed to bring such claims or deny payment on that basis in the past.

While a judge allowed the case to reach a jury and the settlement forces Aerojet Rocketdyne to pay the government $9 million, the agreement also includes a statement that the company denies any wrongdoing, something that muddles the picture around its full legal culpability under the False Claims Act.

“Relator agrees that this … is a compromise settlement of disputed claims and shall not be deemed or construed at any time or for any purpose to be an admission of any fact or liability by Defendants of any violation of Relator’s rights, or any violation of contract or statutory or common law, or of any wrongdoing of any kind,” the settlement reads.

A spokesperson for Aerojet Rocketdyne acknowledged SC Media's request but declined to comment on the settlement.

Dwyer said future cases pursued under the same legal theory by DoJ must go further in demonstrating that the government views noncompliance in cybersecurity as a serious breach of contract.

“I think going forward if the government intends to use the False Claims Act to bring these claims to enforce cybersecurity provisions in federal contracts, that they’re going to have to make it more clear that this something that is material and something that they are expecting to be complied with, otherwise they won’t be making payment,” he said. “I think they can … do more to create the record that this is something with language in the contract and [relates to] the way they behave throughout the life of the contract to make clear that cybersecurity is a material provision, which, culturally, it may not have been 10 years ago.”

Robert Metzger, an attorney and defense contracting expert, noted the monetary penalties are “significant,” especially because the company had to foot the bill for part of the relator’s legal fees, but still “less than I might have expected” given the allegations and amount of time the parties spent in court. The terms of the settlement signals to him that Department of Justice’s civil cyber fraud initiative may have a difficult road ahead leveraging the False Claims Act at scale.

“Taking the length of the proceeding into account, whistleblowers and their ‘relator’ counsel and even the Department of Justice, should temper their enthusiasm for using the False Claims Act as a weapon to ‘police’ contractor cyber compliance,” Metzger wrote in a LinkedIn post this past week. “As I’ve said before, FCA cases are tough to bring and expensive to pursue. There was return on investment here [for the whistleblower and counsel] but it was a long time coming and took a tough, tough fight.”