For some, the horror of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was also meant to mark the dawn of a new era in modern warfare: one in which degrading your enemy’s capabilities through cyberspace would play an important — perhaps even decisive — role in determining success on the real-world battlefield.

As militaries and societies grew ever more connected to and reliant on the internet to run, so too would the cyberspace domain grow in importance in combat, and nowhere was that supposed to be demonstrated more clearly than in Russia’s war, where their elite and well-resourced military hacking units could cut off Ukraine’s access to power, water and other essential resources, disrupt their communications, wipe out large swaths of private and public sector systems and data, and smooth the way for ground troops to dominate their Ukrainian counterparts.

In reality, the impact of offensive cyber operations appears to have been far more muted.

While the initial invasion did, in fact, come with a flurry of hacking campaigns against many of these targets as Russian troops crossed the border, the cadence of those campaigns have dropped markedly in the months following and have seemingly failed to provide Moscow with any meaningful advantage on the ground.

The experience has some U.S. observers advising that we collectively pump the breaks on the idea — formally endorsed by the U.S. military and others governments — that cyberspace is now a fully fledged domain of war, comparable to land, air, sea and space. That’s one of the chief conclusions reached by Jon Bateman, a former cyber specialist at the Pentagon who has served as an advisor to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the secretary of defense on military and cyber strategy, in a paper released shortly before the new year.

“I think it’s fair for U.S. military and NATO and others to define cyber as an operational domain. That can be a helpful doctrinal concept. I think where it becomes misleading is when military and civilian leaders then assume that cyberspace is as consequential or major as these other domains, and that’s why the phrase 'domain' makes me a little uncomfortable because I think, rhetorically, it often carries that connotation,” said Bateman, now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Bateman spoke with SC Media about his paper and what the war in Ukraine can teach us about the proper role of offensive cyber operations in combat.

Cyber “fires” need lots of fuel to be effective

Bateman’s paper evaluates the effectiveness of Russian cyber wartime activities across two main areas: intelligence collection and creating cyber “fires,” or destructive and disruptive cyber attacks on strategic Ukrainian targets, such as the series of wiper malware attacks unleashed on public and private sector in the early days of the invasion and the hacking and disruption of ViaSat satellites that underpinned (some) of the Ukrainian military’s communications capabilities.

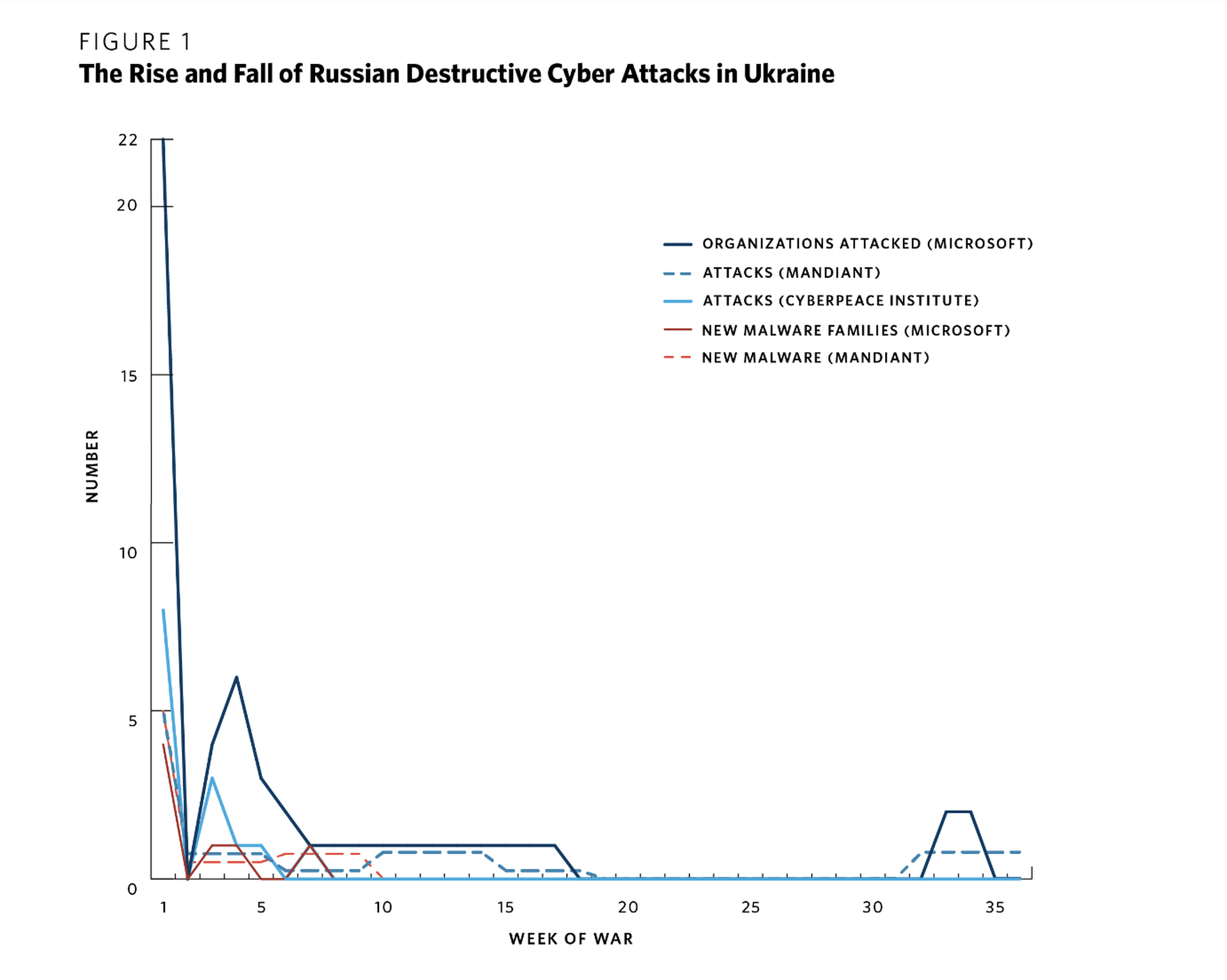

But figures provided by a range of outside sources (including Microsoft, Mandiant and the CyberPeace Institute) show that after that initial spate of coordinated hacks, the frequency and cadence of Russia’s cyber volleys dropped off significantly, from five attacks measured in the first week of invasion to just once a week through October. Mandiant, one of the premiere threat intelligence organizations in the world, tracked just a single Russian cyberattack during a four-month period between June and September 2022.

In any other context, a nation unleashing a different cyberattack every week against another nation would be considered a huge flurry of activity, but Bateman said in the grand scheme of Russia’s war operations — its targets and goals — it’s hard to look at that kind of output as meaningful.

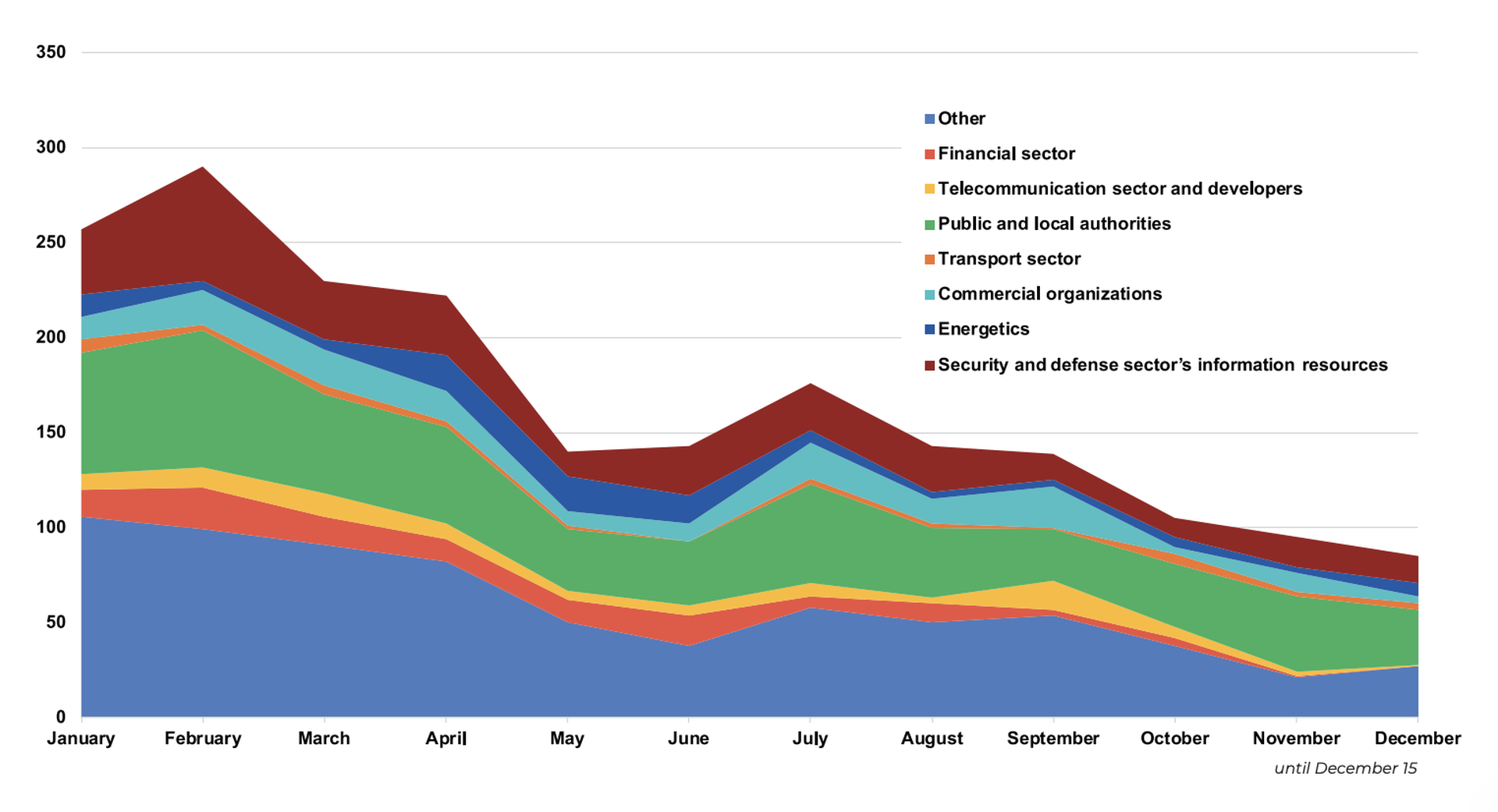

Figures provided by the Ukrainian government at the start of this year show a more active story. According to the Ukraine’s State Special Communication and Information Protection Service (SSSCIP), the number of cyberattacks and incidents registered and investigated by their Computer Emergency Readiness Team since the start of the invasion has surpassed 1,500, though this figure presumably encompasses far more types of activity than the “cyber fires” that Bateman is attempting to track.

Most of the targets for those attacks were Ukrainian civil infrastructure, not military, and the cadence of those attacks has remained relatively consistent throughout the war.

“Cyberattack intensity [by Russia] remains at a certain constant level with minor deviations toward increase or decrease,” the agency said in a January 2023 report.

It also shows how difficult it can be for even an apex predator nation-state cyber actor like Russia keep up that kind of cadence over long periods of time, particularly if they continue to execute on a range of other hacking and espionage-related priorities outside of their war zone.

It looks particularly minor in the face of the kind of disruption and destruction of the enemy’s assets that can be waged with bombs and missiles. For years, policymakers in Kyiv and Washington have fretted about the vulnerability of their infrastructure to cyber-enabled disruption.

“Russia has targeted the power sector, telecommunications, financial sector, media companies, and these events have really put the entire world on urgent notice that protecting critical infrastructure has to be a top national security priority,” Kiersten Todt, chief of staff for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency told SC Media in an interview last year.

That fear led to expectations that a Russian invasion would bring with it a wave of digitally enabled disruption of Ukrainian critical infrastructure and perhaps even U.S. and Western countries supporting Kyiv. That has largely given way to a more conventional reality: kinetic action remains far faster, easier to carry out and more long-lasting.

Russia has been able to affect Ukraine’s power and energy supply, but that has largely been done outside of cyberspace, such as bombing targets with its air force or artillery, or when Russian troops seized control of the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant in a risky March 2022 raid.

“If you do a one-to-one comparison, there is no comparison. Millions of Ukrainians are without power due to Russian missiles. On the other hand, not a single Ukrainian have lost power due to a cyberattack,” said Bateman.

A global conflict brings many caveats

To be clear, there are numerous caveats and unique circumstances surrounding this war that are helping to shape its development and outside perceptions.

First: Ukraine is an unusually resilient target, with its leaders having spent much of the past decade hardening the cybersecurity of the military, ports, electrical grid and other critical infrastructure in the face of relentless Russian attacks in cyberspace following the 2014 invasion and takeover of Crimea.

Those defenses have been further augmented by a swell of financial and military support from the U.S. and Europe and agencies like Cyber Command, as well as assistance from a broad swath of private sector companies with global reach like Microsoft, Google, StarLink, and others providing infrastructure, equipment and technical assistance. Often this assistance is being provided at no cost, with government officials and executives citing a deep identification with Ukraine’s fight against occupation against a longtime Western foe in Russia.

It’s not at all clear how well Ukraine’s cyber defenses would have stood up absent that support. Victor Zhora, head of Ukraine’s State Special Communication Service, told the public in an event hosted by BlackBerry late last year that Russia’s offensive potential in cyberspace preceding the war was “quite scary,” with attacks like NotPetya and Industroyer wreaking havoc on Ukrainian infrastructure.

It's also an open question how much private-sector support other countries — like Taiwan — might receive from those same businesses in the wake of a potential invasion by China, where virtually all these companies are far more economically entangled.

“If you take that foreign support away, the cloud migration, the endpoint security support, Starlink, then yes, there would be a big difference in terms of the efficacy,” Bateman mused. “On the other hand, I don’t agree with those who view any one or all of these foreign sources of cybersecurity support as singularly decisive.”

Bateman also doesn’t discount the possibility that Russia is conducting other clandestine operations or campaigns outside the public view, and U.S. and Western analysts must often rely on the Ukrainian government — a party with a clear self-interest in downplaying the effectiveness of Russian cyber operations — for key accounts and figures. But he also notes that other third parties with their own unique visibility have largely supported the same conclusion.

“I’m skeptical that the reality is very different than what we’ve seen on the surface [of this conflict],” he said. “You can take a company like Microsoft, which has tremendous access to privileged data … and yet even a company like Microsoft which has all the resources and incentives in the world to highlight the most consequential episodes have said Russia’s operations have had limited operational effect.”

Intelligence and espionage remain the best use-cases for wartime cyber operations

There is another major aspect to Russia’s wartime cyber operations that are far less visible to the public and that don’t rely on destructive efforts: intelligence gathering.

For Bateman, the Russian experience bolsters the argument that collecting battlefield intelligence, not setting “cyber fires,” is likely the most natural fit for offensive cyber operations in wartime. That view is largely backed up by Ukrainian military sources: the SSSCIP assessed that the primary goals of Russia’s cyber operations have been espionage and intelligence (such as obtaining logistical information for Ukraine’s military, information operations to spread panic throughout the civilian populace and “maximum destructive effect” of critical infrastructure.

But the war has thus far been defined by a series of brutal setbacks and strategic pivots by Russian troops as they were seemingly forced to abandon plans to capture or encircle Kyiv and have struggled to hold much of the territory they gained in the initial weeks after the invasion. While such cyber-enabled intelligence collection often happens below the level of public consciousness, the many failures of Russian troops on the ground hardly point to the kind of rousing success for intelligence collectors.

“The way I’d put it is intelligence collection is probably the bulk of what Russia has been doing in Ukrainian cyberspace. At the same time, I don’t think it’s been particularly effective for [them],” said Bateman.

Together, Russia’s struggles translating cyber power to on-the-ground war power likely points a need for U.S. policymakers to reevaluate the role that offensive cyber operations should be expected to play in a wartime setting and dedicate more thought to how its unique qualities might be leveraged in armed conflict.

“When I was in the Pentagon I would frequently hear leaders, often people who were not cyber specialists … seem to think of or describe cyber operations as a strategic global strike capability that might be as important for a combatant commander to integrate as a cruise missile strike or something like that,” he said. “I think that’s overblown and that people need to pull back their expectations a little bit.”