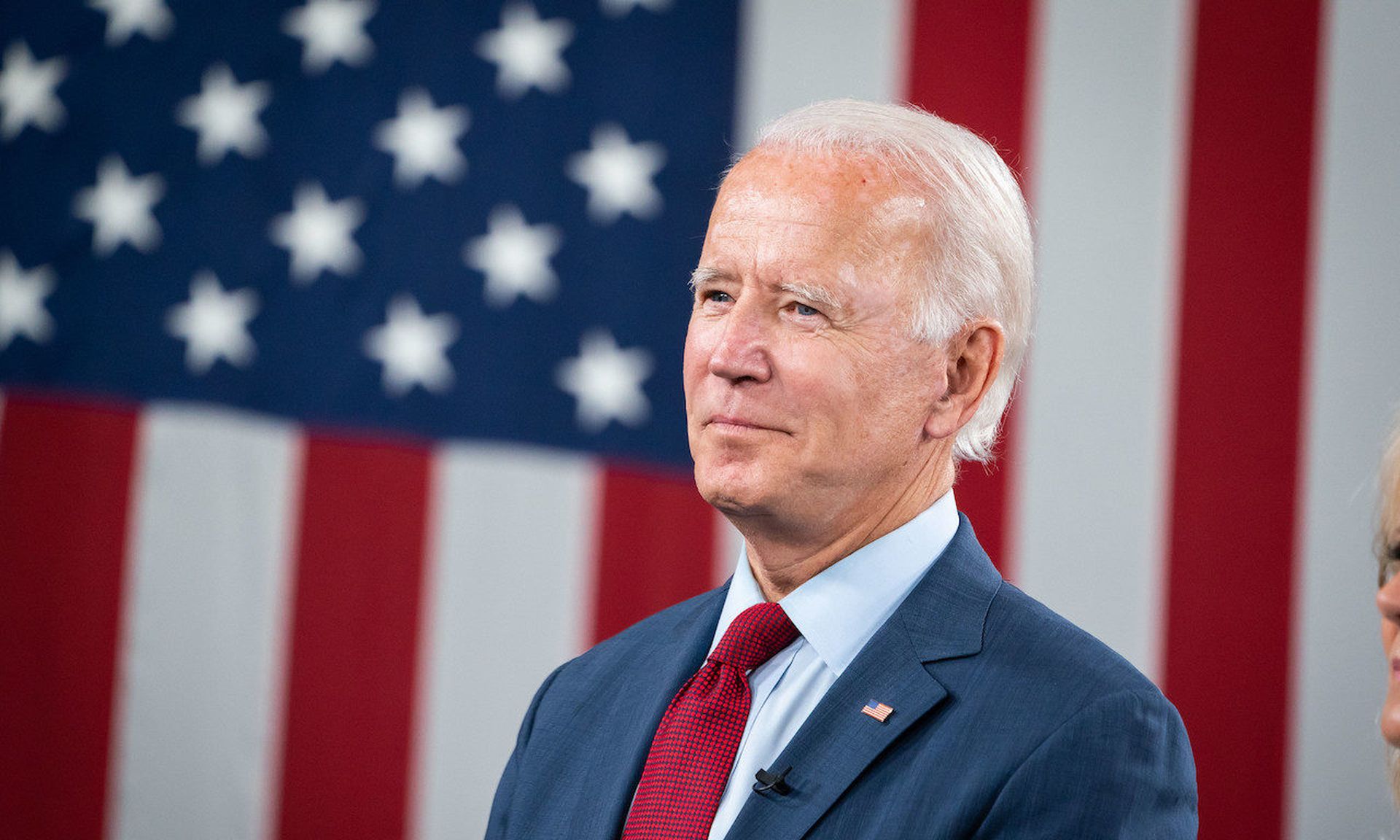

The Biden administration last week finally released the long-awaited Executive Order (EO) that focuses on the rules of the road for software companies that do business with the federal government.

There’s a lot covered in the 20-page document, but the EO’s main focus areas include the following: breach reporting and notification requirements, three days for a critical breach; the government's digital transformation strategy, including zero trust; supply chain security; the creation of a Cyber Safety Review Board based on the National Transportation Safety Board; and response playbooks; endpoint detection and response; and log data needed for investigations.

On the supply chain issue, the crux of the response to the SolarWinds attack, the EO says that “the development of commercial software often lacks transparency, sufficient focus on the ability of the software to resist attack, and adequate controls to prevent tampering by malicious actors.” Does this statement resonate? It resonates with me. The EO almost went through the entire alphabet, with 24 detailed subsections to address this problem. The primary focuses are on practices that enhance the security of the software supply chain, a software bill of materials (SBOM), that defines critical software, IoT security, and consumer software labeling.

For those looking for immediate results off the back of this EO, remember that patience is a virtue. There are more than 45 directives, with the majority having either 60 to 90-day response deadlines. The supply chain section has the most protracted timelines, with four actions at or close to one year out. The phrase “hurry up and wait” seems appropriate.

So why should the average security pro pay attention? Private sector companies are very often like large government agencies. We can apply the Pareto principle here: I contend that 80% of cybersecurity challenges are the same regardless of whether the organization operates in the private or public sector. Does the organization struggle with supplier security? We all are, and over the coming months, quarters, and year, the government will produce content, mainly from NIST, that security teams can take advantage of to improve supplier security. NIST's forthcoming guidelines could likely drive new application security technology adoption in the same way that the PCI DSS has driven the adoption of Web Application Firewalls (WAFs).

B2B companies with government contracts must come to grips that they will soon face significant new requirements. Vendors shouldn't wait for the final requirements; get ahead of the government. The EO lines out capabilities. Do a gap analysis now, and develop a plan. Use the EO as support to drive change if the organization has struggled with application or product security initiatives. Furthermore, the current state of third-party risk management and supply chain security needs disruption; buyers aren't pleased with static risk questionnaires and obscure third-party risk scores. Lean forward, create SBOMs and consumer product labeling now. B2B software firms that are transparent can use supply-chain security for competitive differentiation in both the public and private sectors.

For those responsible for third-party risk, work with the procurement teams to start demanding more transparency and deliverables like SBOMs now. Vendors need to close deals; make this a commercial requirement for all new contracts and renewals. Security teams don't need to wait, there really isn’t time to wait on the federal government. Private industry has collective buying power; take advantage of it.

Think of the EO as a good first step in what I hope will be the last wake-up call in a long line of wake-up calls. Although the administration didn't specifically draft this EO with the ransomware problem in mind, three different sections address vulnerabilities. The guidance could help minimize the risks around known vulnerabilities that ransomware actors target.

There are some challenges with the EO: It doesn't address staffing and training critical for success. We so often try to solve problems with technology alone. Congress needs to sufficiently fund the various agencies, otherwise these initiatives will fail. If we are willing to spend more than $100 million on a single F-35 aircraft, hopefully, we can invest in cybersecurity. Congress might also need to pass legislation to compel vendors to participate in the suggested IoT program. If history has taught us anything, opt-in programs rarely meet the desired outcomes. Rallying behind cybersecurity issues should have bi-partisan support, but Congressional funding and legislation are no guarantee in the current political climate.

Rick Holland, chief information security officer, vice president, strategy, Digital Shadows