Enterprise CISOs are used to worrying about corporate data leaks via typical mobile, remote locations, IoT and Shadow IT. But what about the vehicles used by so many people who have access to the systems and data you are paid to protect? Although those vehicles technically fall into many of those categories (mobile, remote and IoT in particular), depending on the vehicle's make and model, it could be housing phone call logs, precise history of geolocation, contacts, records of chats and email transmissions along with likely identities of people getting in and out of the vehicle, and timestamps for all of the above.

As more semi-autonomous vehicles gain popularity -- and especially as truly autonomous vehicles start to materialize in a few years -- the volume of data that these vehicles will retain will grow sharply.

There are three categories of these vehicles for CISOs to worry about:

- Personal vehicles, owned, leased or otherwise controlled by anyone with privileged network access: a subset of your employees, contractors, partners and customers.

- Fleet vehicles, owned, leased or otherwise controlled by your enterprise and driven by employees or contractors with privileged network access.

- Rental vehicles, paid for by enterprise dollars and most likely driven by a subset of employees and contractors. Ownership is likely by the vehicle rental business.

It's important to delineate those three categories -- and the different kinds of people driving those vehicles -- as CISOs try to decide what they can and should do about the data risks that these vehicles present. Their greatest ability to take control of the vehicle data is with fleet cars and trucks, where an extreme position would be to routinely wipe and/or replace the two data modules that exist in most vehicles (one for the infotainment system and the other for telematics).

Another extreme option is, for extremely sensitive and critical meetings (say, perhaps, the CEO visiting a key acquisition target's CEO at her home, a meeting both executives need to keep secret for the moment), to have burner cars the same way that some have burner phones. That would be vehicles with clean data modules that select people can use for secret meetings and then immediately have the data modules again be wiped or replaced.

When dealing with the personal vehicles used by employees, contractors, partners and especially customers, most CISOs can issue memos that threaten termination if a vehicle is used to access sensitive data. But given the contrary need for maximum efficiency, ease of access and communication speed, that can be a difficult policy to enforce or even to get signoff on.

and forensics manager at Edie Bailly.

Vehicles started getting much more technologically sophisticated about 2008, said Brook Schaub, a former police detective and today a certified e-discovery specialist and forensics manager with a forensic and valuation company called Eide Bailly. Today "you're now up to about 70 computers in each car," Schaub said.

"In the C-suite, there is a lack of recognition of cars as cybersecurity issues," said Shane Curran, a director at Connector APAC, an Australian company focusing on car fleet, mobility, technology and benefits issues. "Cars have have gone from being mechanical object to mobile data devices in a very short time."

Marc Canel, VP of strategy and security at Imagination Technologies, an AI and graphics firm that often deals with automotive issues, sees the vehicle data-retention issue for CISOs as amorphous and challenging. "It is quasi-impossible to know what stays in the car. I personally would never ever use Bluetooth in a rental car," Canel said.

Cars today are also collecting an awful lot of personal information, with glucose and blood-alcohol monitors that won't allow the ignition to start if the numbers are sufficiently good. Combine that with the car's constant tracking of the weight of all passengers (for seat-belt and airbag purposes) and you have a confidentiality issue. Let's say that your enterprise is publicly-traded and Wall Street is chasing rumors about your CEO's health. How would you feel if a car thief could access all of this information and sell it?

Schaub cited one law enforcement case in which the murder suspect tried to create an alibi by leaving his phone in a remote cabin, far from the murder scene at the time of the murder. But by interrogating his car by examining the data modules in the suspect's vehicle, Schaub found lots of evidence of where the suspect was at the time of the crime.

"Take this example: As you enter your car in the morning, the little 'door ajar' light appears on the dash. This activity is now time/date stamped in the vehicle's computers. The vehicle is started and your cell phone automatically syncs to the infotainment system downloading your call list, music, text messages, phonebook and documenting that it is your phone syncing to the system by capturing the device ID," Schaub said. "As you drive down the road, you stop at a red light next to a Starbucks and the vehicle computer makes a record of the free Wi-Fi reaching out to your cell phone. When you pick up a colleague to carpool, once again data showing the passenger door ajar is now recorded. Your colleague has their cell phone's Bluetooth enabled, so your infotainment system sees it, makes a note of it, and decides whether it should try and sync with the phone. It may even document the GPS location where the vehicle was when it recognized the Bluetooth, as well as where the vehicle was when your colleague gets out of the vehicle and the signal is lost."

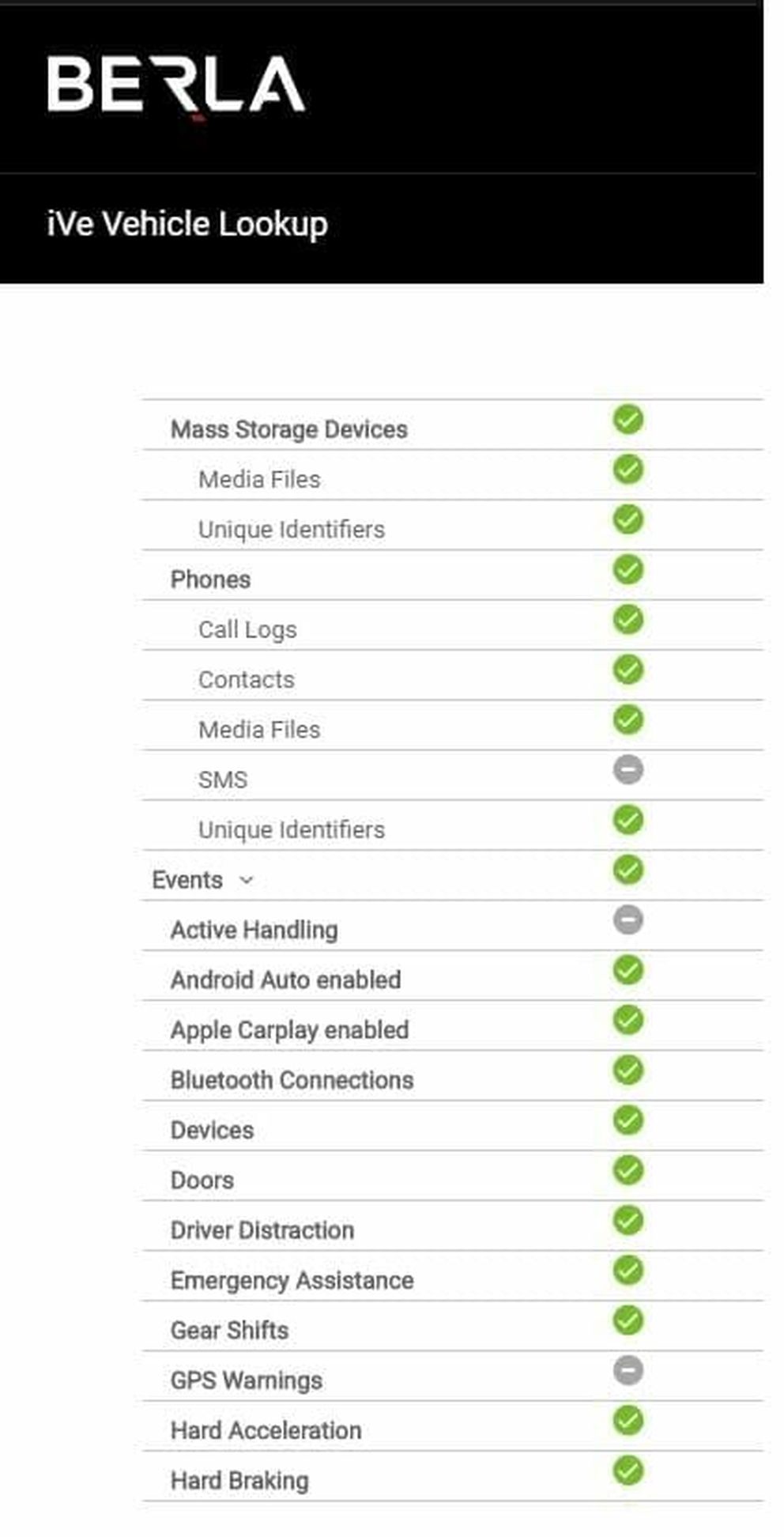

There is an industry public database that Schaub is fond of (https://berla.co/vehicle-lookup/) and that law enforcement typically leverages. The idea is to list as many vehicles as possible and to indicate what data each vehicle is known to retain. It's a good CISO tool, too, especially when investigating potential vehicles to add to your enterprise's fleet. It comes with limitations, though. The free version is limited to a couple of cars a day, whereas a paid license has fewer or no restrictions. Much more importantly, though, the database doesn't list many vehicles.

But it comes through on many. For example, (see screen capture below) it shows that a 2020 Ford Escape retains call logs, contacts, unique identifiers for Bluetooth, mobile devices and Wi-Fi, what is connected via USB, and all navigation locations, among many other things.

A critical complicating factor for vehicle data retention is that some car manufacturers don't have always have an accurate sense of it for their own vehicles because so many of the car's components -- and almost always the vehicle infotainment system, which captures most of the data that would worry a CISO -- are manufactured by third parties. Whether deliberately or not, those components may retain more than the car brand is told. The only way to tell is to do what a pen-tester would: access both data modules and see exactly what data is inside.

As with so much of security, automotive data security involves a variety of "choose your poison" decisions. Depending on the car make/model/year, car data retention is minimized if a mobile device is disconnected at the end of a trip. But even the car doesn't retain it, that data is available to the phone's handset manufacturer, operating system company, app developer and sometimes the carrier. Some navigational systems' data stays on the phone, but some car native navigational systems will track the vehicle's location anyway. If an employee chooses, for example, to use Waze on an iPhone, they could be exposing their data to both Apple (which owns iOS, the iPhone's OS) as well as to Google, which happens to own Waze. It’s enough to drive a CISO crazy.

Curran offered some other vehicle data retention concerns. With semi-autonomous and especially fully autonomous vehicles, not only is there the need for far more data usage, but the places for it to leak are also great. Such vehicles need to know what every vehicle around them is doing and any particulars about those vehicles. They will query each nearby vehicle and ask it for whatever it can, offering data about itself in the process, Curran said. The intent is to help the system make life-and-death decisions, such as which vehicle to crash into in an emergency. The system might think "Hmmmm. Tiny Toyota versus Mack truck. I'll lose. Therefore, if I need to, I'll hit the Honda on my right."

Said Curran: "The risk is that because the data is so widely shared, it could include data that you don't intend to share."

Another Curran fear: Foreign state data access. He cited China as the current largest car manufacturer on the planet, but of much greater concern is that Chinese companies are positioned to create many components for all of the other large vehicle manufacturers. If those components try to retain data that they are not supposed to, Curran argues, it could potentially create corporate espionage issues.

Jeff Hall is a senior consultant with Wesbey Associates, which specializes in security issues and especially PCI compliance and healthcare cybersecurity. Hall cautions CISOs to be extra-cautious with automotive systems to trust anything.

"Google and Apple are responsible for their particular integrations with these infotainment systems and their devices. None of the vehicle manufacturers make their infotainment systems. They contract with manufacturers including Denso, Delphi, Alpine, Continental, Harmon, Panasonic, and others. The OS in a lot of these systems is Blackberry QNX, Linux or even embedded Windows but Google is making inroads with their Android Automotive OS, which will show up in GM vehicles in 2021," Hall said. "Even the application software like MyChevy, Cadillac User Experience (CUE), Ford SYNC, Chrysler Uconnect and the like are all contract produced out of some software development center in the world. Granted, all of this is subject to the vehicle manufacturers’ specifications, but they build none of it. All they do is install it into the vehicles on their assembly lines. So you tell me: how you trust any of it?"