It starts out innocuously enough when an important-looking email comes in to a company employee. The sender’s email address is that of the company’s CEO, claiming that a payment needs to be made to a client or vendor immediately.

The email, which contains some sense of urgency, tells the employee to wire transfer an amount of money, perhaps $50,000 or more, to a specific company or bank account. The reasons vary but follow a common theme: A vendor has a new bank account and prior payments to that vendor failed. The company is “late” on its payments and a purchase needs to be made for necessary products or services. Whatever the purpose, the CEO does not have the time to go through normal check-request procedures and requires a quick response.

Often these requests are made when the CEO is out of town (the CEO’s or company’s own social media accounts might have mentioned he or she is at a conference or traveling on business — attackers have a lot of ways to determine when an executive is traveling) and confirmation might be difficult. So, in response to an email that looks like it comes from the CEO, the company employee immediately processes the check request and sends the wire transfer. The underlying concern for the employee is that if they do not process the request, their job could be in danger.

Poof. A relatively untraceable wire payment was just made to cyberthieves who just pulled off a quick scam by playing on the emotions, worries and goodwill of an unsuspecting company employee. The company was just victimized by a CEO fraud email attack, also known in law enforcement circles as a business email compromise (BEC) attack.

It could never happen to us in our business, say many executives. Hogwash.

It can and it does happen every day and it likely will continue to happen inside businesses for as long as cyberthieves play their emotion-throttled games with unsuspecting victims within companies where adequate training, policies, and procedures are lacking.

The FBI has been tracking these kinds of business email fraud attacks since 2013 and reports that companies have been victimized in every state and in more than 100 countries around the world, according to the agency. These crimes have happened to nonprofits, Fortune 500 corporations, churches, school systems and other businesses.

The global losses in 2018 alone are expected to exceed $9 billion from these crimes, according to a recent analysis from one cybersecurity vendor. That is up from $5 billion in such losses that were predicted by the FBI for 2017, and nearly triple the estimated $3.1 billion in global losses that were seen in 2016.

So, what is the root of the problem and how can it be curtailed or stopped?

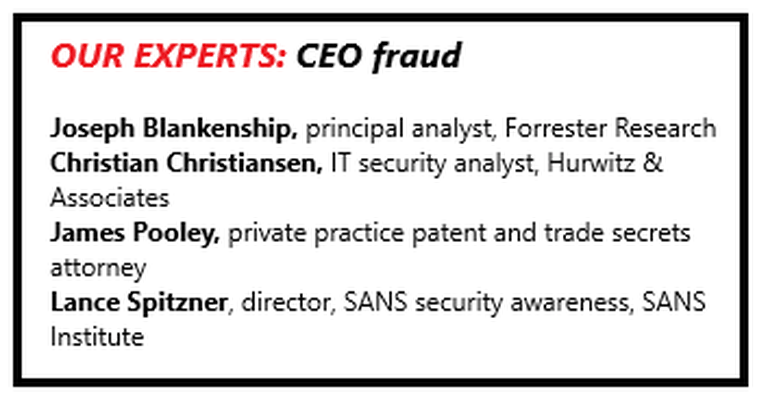

“This is not a technology attack; it’s a psychological attack,” says Lance Spitzner, director of SANS security awareness at the SANS Institute, a security research and education group. The methods for stopping the attacks remain the same as they have since they began, says Spitzner: Start by training employees to view all suspicious emails, especially those with a rushed or emergency tone and unusual requests, as fake emails that are trying to steal money from the company.

Essentially, he says, employees need to be taught about the clues and indicators that point to email fraud attacks and then to always follow established procedures in response, such as verbally check with the CEO or other senior staffer to confirm that they sent the request.

director, SANS security awareness, SANS Institute

While this type of attack is often called “CEO Fraud,” it could refer to any senior executive who is being impersonated by the attacker in order to get a lower-level staffer to take a specific action. Sometimes the action itself is not sending money; it could be a request to unlock a door that is normally locked (creating a physical breach vulnerability) or perhaps sending employees’ personal information, such as W2 tax documents or pay stubs, to a non-company email address in order to steal employees’ identities.

The employees must be trained carefully not to give in to emotions under stress when the resourceful and convincing thieves try to get them to respond by sending money, no matter what the threats or pleas are from the attackers, says Spitzner. “Their level of commitment to withstand the attacks rivals that of the guys who hold nuclear codes,” he says.

Establish codes

Clear policies and procedures are necessary for employees to use in order to confirm a request that seems unusual or perhaps sets off pre-determined policy alarms are triggered, experts agree. However, for these policies and procedures to be effective, it is essential that the senior executives who might be spoofed in the malicious emails — the CEO, president, CFO or other senior executives — agree to respond if an employee is doing their due diligence and requesting that the executive confirm a request made by email or text message, says Joseph Blankenship, principal analyst, at Cambridge, Mass-based Forrester Research. Companies must foster a work environment where no worker will be criticized, hassled or challenged when they inquire about such messages.

“People are often scared to challenge the CEO” by making such direct inquiries, which is what the cybercriminals hope will occur, he says.

One way to battle attackers is to establish clear and concise code words or phrases that can be used by the real CEO or other senior executive to authenticate his or her identity in an emergency. If the established code words are not known and repeated exactly by the attackers, then the employee can have a strong indication the email request is fake and they can reject it without concern about being fired for not following orders, says Christian Christiansen, an IT security analyst with Hurwitz & Associates of Needham, Mass.

IT security analyst, Hurwitz & Associates

“It seems like CEO fraud is just the phishing attack that keeps on taking via wire fraud,” says Christiansen. “There are many solutions, even some that are tech-free, but people seem to mistakenly continue trusting email.”

That is where using secret codes, such as a few words in a pattern or specific statements about any topics that are known only to the real CEO and their employees, can be particularly effective to authenticate an email sender, he says. Also important are creating and maintaining financial transaction procedures that say that no wire transfers can be initiated solely by one person, regardless of who that single individual is. Instead, controls should be added so that all such transfers require a second or third person to authorize them over a certain amount, or if the money is being sent outside the United States, says Christiansen.

Similar controls should also be placed on corporate credit cards to prevent employees from having to be placed in these situations where they must make judgment calls during such attacks, he says.

Today’s attacks feature the same hallmarks as previous incidents, with the attackers conducting a wide range of basic research on the CEO using internet searches, often revealing travel plans, hobbies, favorite sports teams and other information the attackers use to try to bluff company employees and get them to think they are the person they are pretending to be. While companies strive to provide transparency about their organizations, attackers use this data to build more effective attacks.

Elevated privileges

While employee training for scenarios like these is critical, security teams need to remember to look at the company’s email traffic carefully so they can flag or spot any suspicious behaviors, particularly involving workers who are in the accounting, accounts receivable or other sensitive departments, he says. Instead of simply accepting emails from all domains, consider blocking suspicious ones from places where your company does not do business, Christiansen says.

“[For] people who have higher levels of financial access to your systems, you want to look and monitor those people pretty closely, people with elevated levels of privilege,” says Christiansen. “Often there can be coercion by attackers, or [attackers] can buy them drinks at a bar and ask about the company and its executives.”

Attempts to compromise corporate employees do not only focus on high-level executives with access to company secrets; systems administrators with privileged access to servers are often targets because their login credentials provide attackers with access to move through systems laterally without raising red flags. A compromised email administrator’s credentials, for example, could provide access to legitimate email accounts, making CEO fraud appear that much more legitimate.

Of course, companies must ensure that other basic but often neglected procedures are conducted, such as patching all desktop and laptop computer systems and related business infrastructure to protect them from succumbing to a wide range of security vulnerabilities. While it might seem easy to point to patching as a best practice, network administrators will tell you that before patches are moved to production systems, the IT team must ensure that the patch will not break some other system software. That time between delivery of the patch and how long it takes to verify it won’t break other applications often can be the difference between identifying a vulnerability and falling victim to it.

Another recommendation is never to call the phone number provided with a suspicious message. If employees want to reach the person requesting an unusual wire transfer or other action, they only should call the individual’s authenticated phone numbers to confirm the email’s request. Otherwise, they might end up calling a phone number being used by the cyberthieves themselves as part of the scam.

Use a holistic approach

Forrester’s Blankenship recommends using a holistic approach to battling CEO fraud email attacks, including knowing and recognizing the threats, stopping or flagging suspicious messages and effectively educating employees on how to circumvent such attacks.

Email filtering is often not effective enough on its own because the attackers usually mask their exploits and make them quite difficult to detect and filter out, says Blankenship.

What email filtering can do, however, is detect known spam and commodity phishing emails that have been reported or detected by others and stop them cold, he says. “What’s missing is the ability to detect suspicious emails or make targets aware that an email or other communication may be fraudulent. Some vendors are using machine learning and artificial intelligence to detect these, but the technology isn’t perfect yet and most businesses are not employing it.”

principal analyst, Forrester Research

Ultimately, because the known detection methods today are not foolproof, it is up to the email’s recipient to decide if a suspicious email is fraudulent or not, he adds. That can create its own conundrum: “Smart attackers will research their targets ahead of time and will work to gain trust before actually asking the target user to do something.”

To fight clever attackers, recipients must verify that incoming emails are real before taking any actions requested by the message, which is not easy to do during a busy and stressful work day, says Blankenship. “It’s up to security professionals to make sure their users and executives have the tools they need to defend themselves. Leaving it solely up to the user is doomed to fail.”

Depending on the size of the company and its internal IT organization, these needs can produce their own challenges because threat controls and training might not be available, he says. “Unfortunately, in a lot of these cases, these are typically mid-market or SMB companies, so they don’t have a big IT team fighting for them.”

In such cases, companies can subscribe to an ongoing security service for help, especially if they can provide real-time threat feedback, he notes. Another effective practice is to conduct regular procedural drills for employees so they can learn how to respond properly and securely to incoming “bait” emails that purport to be from the CEO or other executives.

One complication today is that since business email compromise attacks have persisted for years, plenty of data from past attacks is out on the internet and is available to be reused by today’s bad actors, says Blankenship. “All that data is floating around out there, so names and data are available. It becomes that much easier for a criminal to use that for their own means.”

Protecting company information

In the end, everything companies do to fight CEO fraud/BEC attacks is about protecting their businesses, employees and their operations, says James Pooley, a trial lawyer in Menlo Park, Calif., who specializes in trade secret and patent litigation.

Training employees to react to probing emails that come in with suspicious messages is one of the things he speaks about often with executives inside companies as they work to safeguard their IT systems.

One tactic he recommends is to set up carefully crafted protocols ahead of time so that incoming suspicious emails can be halted early in the process, says Poole. The protocols should include specific rules about any interactions that might come directly from the company’s CEO and other high-ranking executives, such as if an executive asks for money to be sent using specific instructions that might deviate from the norm.

Underscoring the need for code words to authenticate an instruction, Pools says the protocols might include “you will only get messages from me on these kinds of issues with this specific password or marker that can’t come in from the outside.”

Some new data loss prevention tools are using artificial intelligence (AI) to help weed out these kinds of attacks from cybercriminals, he added. “They are using AI that analyzes the nature of the communications themselves in ways that are far more sophisticated than just looking for words that match filtering lists. AI is really the way forward.”

So, will future CEO fraud email attacks ever be completely blocked? Not likely, says Poole. “If an outcome is affected by human behavior, you can’t 100 percent prevent errors by people. All you can do is try to react.”

The email fraud attacks “play on the fact that we are very busy and we don’t stop to question something that on its face has markers of plausibility,” says Poole. “Life is very fast these days, including inside the corporate environment, and people need to get things done now.”