This story, which was originally published in October, has been updated to reflect the results of the presidential election

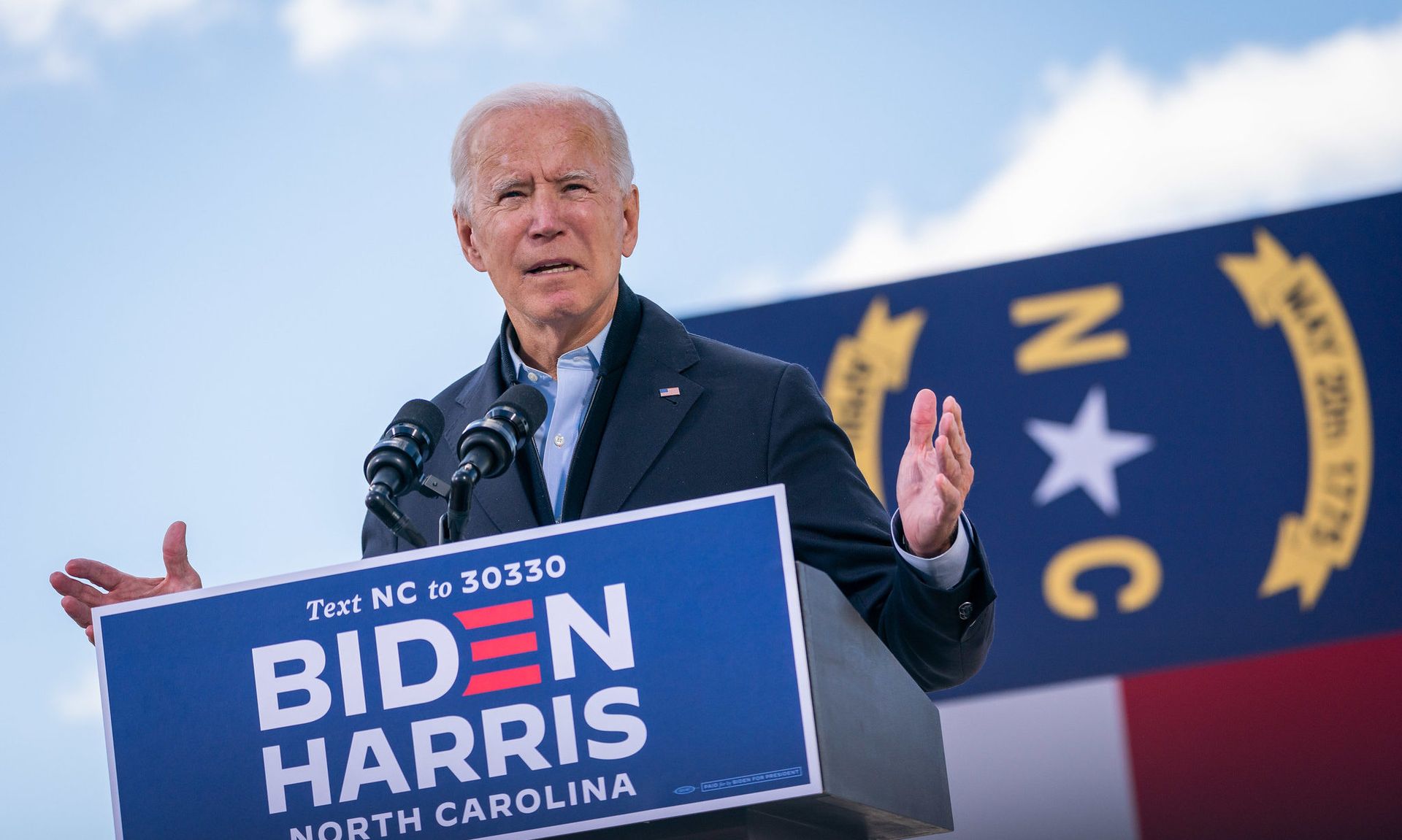

Even among those who have worked with him, Joe Biden is not known as a tech policy wonk.

So, it's not surprising that, during a pandemic, cybersecurity didn't come near to the top of the list of topics Biden's campaign prioritized for the sake of the election. Russia's election meddling may get a mention, but nothing tied to any substantive cybersecurity policy.

That said, any president’s potential influence on cybersecurity policies are manifold, with legislation, trade philosophy, and even military actions all playing a role. And as the cybersecurity community assesses a Biden White House, privacy regulations, global internet surveillance practices, and supply chain security are all at play.

Those topics matter to practitioners like Michael Daly, chief technology officer for cybersecurity, special missions, training and services at Raytheon Technologies. But what he says matters most is whether the government prioritizes cybersecurity in the first place.

“It's just a question of how much focus it gets – how much energy anything can get in the time of COVID-19,” he said. “There isn't a lot of oxygen left. But I’m hoping that cybersecurity will see a resurgence in importance.”

SC Media spoke to numerous sources, many who worked with the former vice president or his running mate Kamala Harris, about how cybersecurity might enter the conversation in the White House.

What new leadership can and can’t change

Much of the government cyber posture is handled by agencies, including the departments of Homeland Security and Justice. And while there are often brash changes to leadership, the cybersecurity priorities remain very similar and long-term plans remain in effect.

“I don’t think who’s in office changes many of the goals, but there’s a change in focus and energy,” said Daly.

Former DoJ employees note that many of the prosecutions of Chinese hackers for economic espionage that we see today, for example, are the result of strategies and investigations put in place in prior administrations, sharpened by Chinese actions and new lessons learned. The same is true for much of DHS’s work through the Cybersecurity and infrastructure Security Agency, or CISA. And just as strategies need time to develop, successes and failures can often be attributed to career officials, not changes at the top.

For day-to-day work, several former government employees say, agencies adapt more to changing threats than changes in leadership.

“The Obama administration built on some really great work that was done during the Bush Administration, which built on some good work that was done during the Clinton administration,” Obama-era Federal Chief Information Security Officer Greg Touhill and current president at AppGate Federal told SC Media. “And Grant [Schneider, Touhill’s successor appointed by Trump] went from being my deputy to carrying the same message into President Trump's executive order as well as the national cybersecurity strategy.”

But leadership changes have a more profound effect on how information gets to the president and how the president weighs the different priorities of different agencies and of industry partners. A Biden pivot back towards a more traditional, full collection of White House advisers, including restoring dedicated cybersecurity staff, could ensure that the issue doesn’t get lost during a presidential term dominated by recovery from a COVID-19 shattered economy and several national disasters.

“Any administration will tell you one of the single most precious commodities that it has is time,” said Michael Daniel, former Obama cybersecurity coordinator and current chief executive of the Cyber Threat Alliance. “To the extent that you can count on people whose job it is to continue making progress on policy issues, even in the midst of other stuff going on is very important; to say, ‘hey, if we want to avoid the next crisis over here, let's take five minutes to talk about this.’”

During the tenure of John Bolton as national security advisor in the Trump Administration, the National Security Council dramatically reduced staff in the hopes of streamlining decisions. Many government officials of both parties see value in a president reintroducing and utilizing something akin to the cybersecurity coordinator position that was eliminated – that is, someone to make sure all agencies are rowing in the same direction and to coordinate with the private sector. Biden may be inclined to do that, considering a cybersecurity coordinator existed under the Obama administration.

“One thing I learned in the military as a cadet, is the best way to get a bunch of people from over here to over there is to have somebody call cadence,” said Touhill, who served to the rank of brigadier general. “You need to have that coordinator who's making sure that we are in sync, for example, with offense and defense. If I've got Cyber Command firing cyber shots down range, you know what? They're going to shoot back.” Agencies and businesses need to be prepared when that happens.

That could also serve well what many expect to be a more deliberative and measured approach to government that will come from Biden, much like Obama. That approach relies heavily on both public and private sector stakeholder input. It means, for example, that someone from the Department of Transportation may be aware of U.S. action that could lead to a counterattack on airports. More thorough legal review could ensure better outcomes in court cases.

But it all comes at the cost of expediency. And cybersecurity decisions aimed at any one sector – including government – often have broad impacts on other sectors.

“It's frustrating and it's sometimes slower than you would like, but I firmly believe you end up making better policy,” said Daniel. “They can stand the test of time that way” for both government and the businesses community.

Privacy policy

Privacy policy in America is a patchwork of several legislative efforts siloed by industry. It’s a key issue where the government, and not an industry group, creates the standards that industries have to abide by.

“The biggest and most obvious focus is in compliance, especially around privacy,” said Raytheon’s Daly.

Harris has a more robust tech policy lineage than Biden, particularly around privacy policy. In 2012, as attorney general of California, Harris set up the Privacy Enforcement and Protection Unit, helping the state become a national leader in regulating consumer privacy.

Her vice presidency will come at a time when corporations and civil liberties groups alike are asking for a national privacy policy on the scale of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – the regulation governing data protection and privacy in the European Union. For businesses, the alternative is 50 different and potentially contradictory state laws for chief information security officers to juggle.

In the words of Daly, “it’s far cheaper to have one set of rules.”

Harris will also bring some experience to the delicate negotiations with tech companies.

“During a time when mega breaches impacted consumers at a very personal level, her office took the lead on several of those investigations,” said Kathleen McGee, an attorney for Lowenstein Sandler who handles cybersecurity and tech issues. She formerly worked with Harris’s California attorney general office as chief of the Bureau of Internet & Technology for the New York State Attorney General’s Office.

“Along with several other states, California entered into what were groundbreaking agreements with companies that paved the way for a greater level of expectation” from customers, she said.

Privacy policies affect what data companies can save about consumers, how it must be stored, when consumers must be explicitly notified about a data incident and how data can be sold on a lucrative secondary market.

Democrats have traditionally been the party most in support of bringing U.S. positions on privacy in line with those around the globe. The EU, for example, views personal data as personal property even when it’s stored on a commercial site. That dramatically impacts the data economy that keeps sites like Google and Facebook in business. As emerging technologies like biometrics work their way into storefronts, like Amazon’s cashierless store concept, those concerns can heighten.

Harris comes from California and has represented Silicon Valley in the Senate, McGee noted. It may give Harris a unique credibility for both sides of the debate. And credibility might be a key, missing factor in getting a privacy bill passed. National privacy policy was at times a priority of both the Obama and Trump administrations, but got little traction.

Larry Clinton, president and CEO of the Internet Security Alliance, which lobbies for cybersecurity policy on behalf of a broad swath of companies, expects federal agencies to take back regulatory power the Trump administration abandoned in a new administration. And, he said, that might not be a bad thing.

“Industry is more risk tolerant than the government. Why does 10 percent of product walk out the door? Because cameras and security guards cost 11 percent,” he said. “But commercial insecurity creates a national security threat.”

International considerations

The Obama-Biden administration – and, most politicians before Trump – typically approached multilateral global agreements so as to benefit all parties. Under Biden, attempts will likely be made early on to repair some of the relationships fractured during four years of an America First philosophy.

But why might that matter? While global relations may seem more a matter of diplomacy, they can often influence cyber activity for both the government and the business community.

“When I advise companies, I say ‘don’t just read the science and technology pages,’” said Michael Bahar, an attorney for Eversheds Sutherland with a focus on cybersecurity and technology policy. “Read the front page, because often when geopolitical tensions rise your work is going to be hard” – and vice versa.

By promoting the idea of sovereignty over international cooperation, the United States has lost some of its influence to combat global shifts in internet governance. There has been a slide toward the Russian and Chinese ideal of a nationally siloed internet: less open, more surveillance and fewer global cloud offerings. All of those policies are less attractive to global businesses that depend upon the availability of such services to support operations.

“I would hope to see the U.S. regain some of its standing as a leader internationally in developing good cybersecurity policies,” said Daniel. “Biden would move against some of the balkanization that China and Russia have made in the past few past four years.”

A coalition of allies could influence the world away from the Russian and Chinese version of Walled Gardens, he continued, "where the government gets to decide who sees what, who gets what, what kind of information moves." That would swing the pendulum back to a more comfortable position for businesses, which must track global data and surveillance policies that could impact supply chains.

Notably, China’s international dominance of supply chains – with equipment embedded in everything from computers to the telecommunications equipment to emerging social media platforms like TikTok – creates massive uncertainties in the business community. It also introduces an array of security concerns.

Daniel offers that a unified crackdown among allies on China might mean, in part, offering alternatives to Chinese products, and may mean building a domestic 5G equipment industry to counter Huawei.

The Internet Security Association's Clinton believes China has pushed the U.S. to an inflection point, which will force cybersecurity and general technology policy to be reconsidered. The White House will be compelled toward collaboration with companies, and toward funding of domestic research into fields like machine learning and quantum technologies – those areas where he feels the next Huawei skirmishes will happen.

As Clinton stated: “It matters who the leader is."