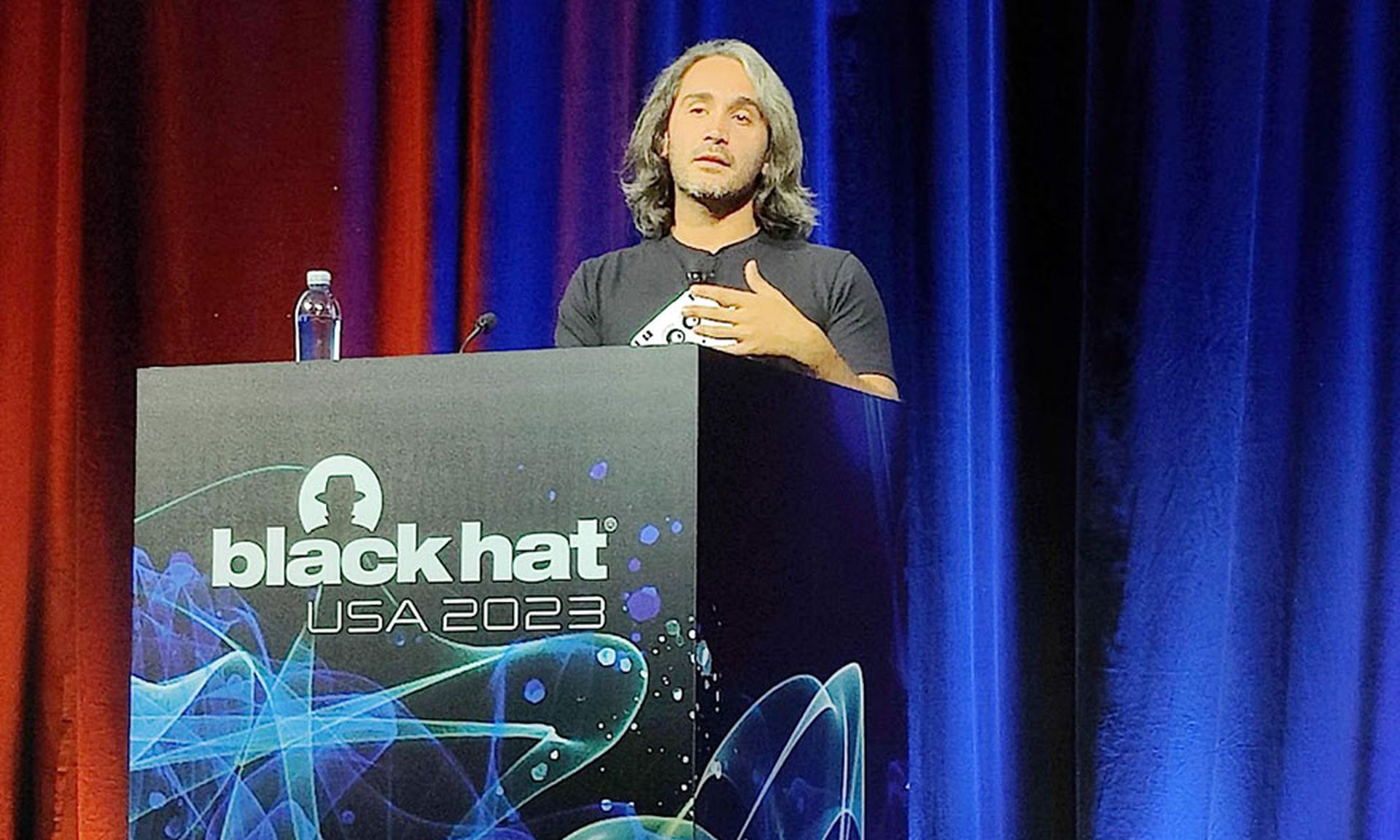

LAS VEGAS — A hardware flaw in Intel Core and Xeon CPUs lets attackers steal data from other users on the same system, including on servers that use Intel's SGX memory protections, Google researcher Daniel Moghimi told the Black Hat 2023 security conference.

The vulnerability, dubbed "Downfall" by Moghimi (and given the cute mascot below, as well as its own web page) endangers data running on virtual machines or in containers in shared environments, such as in most cloud-computing deployments, as well as on personal computers with multiple users. Information-security purists will refer to the flaw as CVE-2022-40982.

"A malicious app obtained from an app store could use the Downfall attack to steal sensitive information like passwords, encryption keys, and private data such as banking details, personal emails, and messages," wrote Moghimi on the flaw's web page, posted the day before his Black Hat talk. "Similarly, in cloud computing environments, a malicious customer could exploit the Downfall vulnerability to steal data and credentials from other customers who share the same cloud computer."

"A single hardware vulnerability undermines all security boundaries," Moghimi told the Black Hat audience.

Six generations of vulnerable Intel chipsets

Downfall affects Intel CPUs ranging from the Skylake (6th-generation Core, introduced 2014) through the Tiger Lake and Rocket Lake (11th-generation Core, 2020) chipset families, as well as Xeon CPUs from the same microarchitecture families.

Alder Lake (12-generation Core), Raptor Lake (13-generation Core) and related Xeon chipsets are not affected, and nor are the new Sapphire Lake Xeon chipsets. (Intel has posted a guide to which chipset families are affected here.)

Affected Intel chips will have to implement a micropatch provided by computer and server makers, but that could result in a slowdown of up to 50%, depending on the application. Moghimi said some specialized patches, such as for SGX, will not be ready until next month.

Alder Lake and Raptor Lake's immunity appears to be the result of a happy accident, explained Moghimi, as the 12-generation chipset was released in the fall of 2021, nearly a year before Moghimi privately disclosed his findings to Intel in late August of 2022.

The vulnerability lies in the "Gather" instruction in Intel chips that is meant to access scattered data in memory more efficiently, Moghimi said. Gather is used by Intel chips to speed up fast data processing, and any application with such needs takes advantage of the instruction.

An Intel Core CPU can speed up Gather by reusing data from same cache line, or by preserving partial instructions if there's an interrupt, Moghimi explained. However, it can also take a shortcut by forwarding data it has, well, gathered to the next likely instruction set before the Gather instruction itself has completed.

If you were paying attention to Intel chipset flaws five years ago, this sounds ominously familiar.

"Shared buffers forwarding data speculatively," observed Moghimi. "What could go wrong?"

What's old is new again

Indeed, Downfall is broadly similar to the Spectre and Meltdown flaws that convulsed the information-security world in the winter of 2018. Like those vulnerabilities, Downfall exploits speculative execution to force "bleeds" of data across seemingly impermeable boundaries.

In this case, the flaw seems to be a result of Gather using a single buffer to plot speculative execution across all CPU processes, regardless of user. That makes it possible to guess the contents of the internal vector register file, which points to data belonging to other virtual machines.

Moghimi was able to exploit the Gather instruction so that one of his virtual machines was able to steal data, including OpenSSL encryption keys, from another virtual machine running on the same processor.

Moghimi's dedicated Downfall page has a clear FAQ explaining the scope of the flaw, and also links to a highly technical paper on Downfall that we foolishly tried to understand. Intel has copious documentation, including this guide to Downfall mitigation.

Intel refers to the flaw as Gather Data Sampling, which is also what Moghimi calls his exploit technique. You can download the exploit code from GitHub.

"Even if you do not own any physical Intel-based devices, Intel's server market share is more than 70%, so most likely everyone on the internet is affected," Moghimi wrote on his explainer page, adding that Downfall-based attacks would be very difficult to spot.

"Downfall execution looks mostly like benign applications," he wrote. "Theoretically, one could develop a detection system that uses hardware performance counters to detect abnormal behaviors like excessive cache misses. However, off-the-shelf antivirus software cannot detect this attack."