It’s time to take fully homomorphic encryption seriously, according to Eric Maass, director of strategy and emerging technology at IBM Security Services.

Maass spoke to SC Media in advance of IBM’s Thursday announcement that the company would provide training, an online sandbox and consulting services for developers looking to get a head start on the emerging technology.

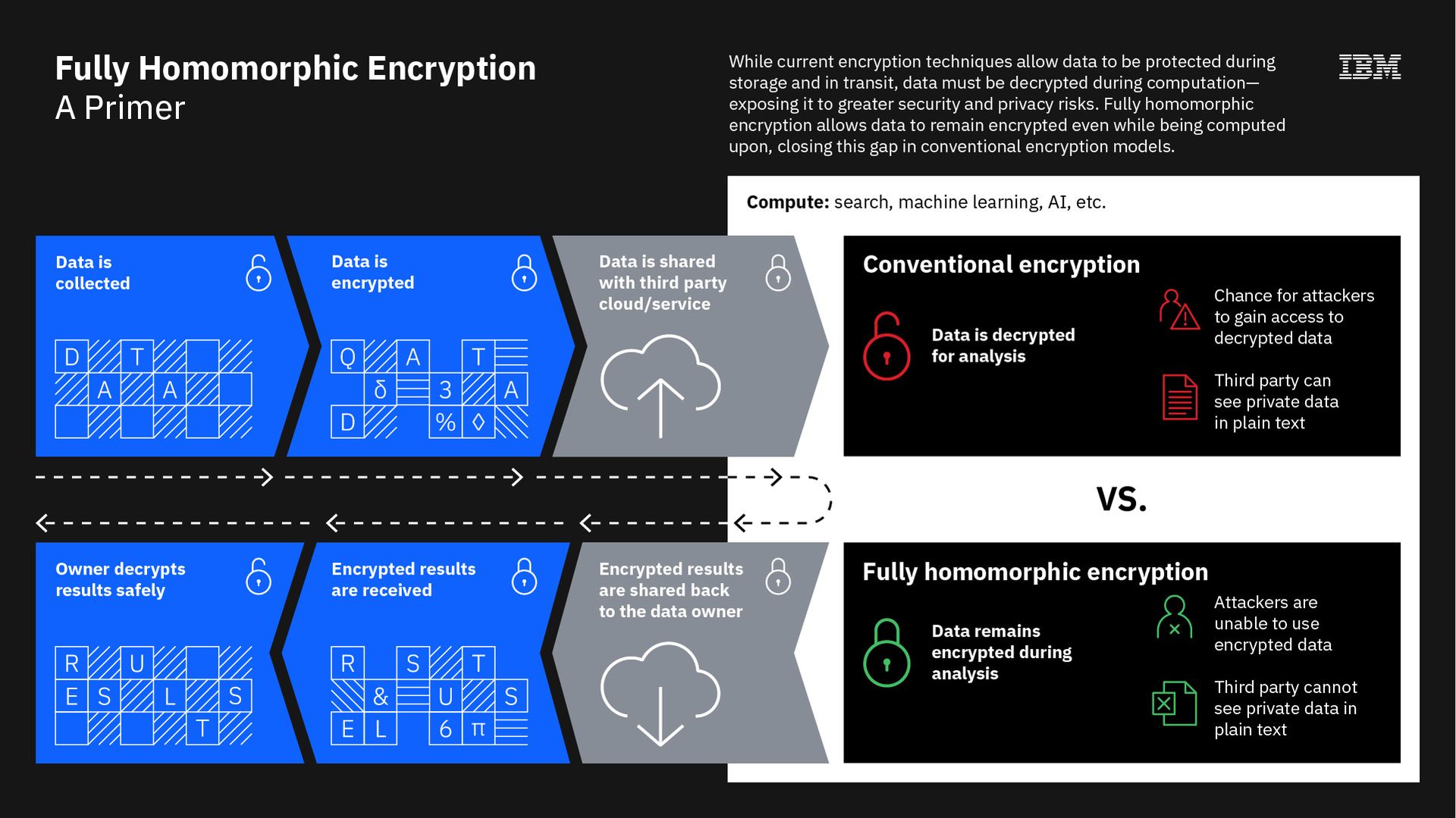

But what is homomorphic encryption exactly? In a nutshell, the capability allows computers to perform operations on encrypted information without decrypting it – meaning data science and machine learning are possible without actually seeing the data. There are clear advantages to using it in any process that requires data sharing or auditing.

“Let's say you are a bank. and part of the organization wants to do something like training [for] fraud detection, based upon banking data,” said Maass. “You know giving part of the organization all your real client data is pretty risky to do. Same thing with a health care provider allowing clinical researchers to look at patient data to be able to study a disease. It’s very risky to give real patient data, but it's necessary in order to do real research.”

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) has long been viewed as a technology perpetually 10-years away, due to its drain on computational resources. It’s a part of that “going to get here soon, I promise” class of products, that included quantum computing and machine learning until advances made one firmly realistic and the other market ready.

Maass said FHE is also at that precipice. It’s close enough to start preparing for the technology to implement at scale. He estimates 18 to 36 months before we see general use.

“We are bridging it out of the lab,” he said. “Really the next lead of improvements is going to come from interacting with real-world clients.”

“If we rewind just five or six years it would take thirty minutes or so to process a single bit of the encrypted data. We made some breakthroughs, and can process a complete human genome in an hour today. We're at the point where typical processing may be somewhere between 25 to 50 times more intensive, and doing something really complex, like training machine learning, may be several hundred times more computer-intensive than a clear text equivalent. But that's coming down substantially.”

FHE differs from partial solutions in that it can perform all operations on data – add as well as multiply – to provide limitless functionality.

But while the functionality can be similar, the architecture takes some getting used to; it takes some work for developers to adapt.

“We have a very strong focus on the consulting side in what we're announcing, to be sure we can educate, bring developers up to speed, because the differences will kind of bend the minds of the conventional developers,” he said. “Some of the things they’ve been taught they are able to do are not going to be possible.”

The next steps, he said, will be to improve accessibility. The workers developing internal or external business applications need to understand the ins and outs of the technology. Data scientists probably will not, and would probably do better once companies like IBM can offer the kinds of simplified, albeit less powerful development environments they are used to.

While FHE solves many of the problems with data sharing, security and privacy, regulations have not caught up. Privacy laws were not written for a world where data could be shared without being read, and questions of FHE changes the debate over anonymizing data sets.

“IBM is going to be working closely with regulatory agencies to start to get their head wrapped around this, and say ‘technically yes, we're giving this data away, but here's why we're not giving that data away in a way it would be usable,’” he said.