The emergence of Grief, a new ransomware program with a possible connection to a U.S. government-sanctioned cybercriminal outfit, raises an interesting question: If you make a ransom payment to an unknown adversary that only later is confirmed to be a cyber terrorist group, can you still face penalties?

According to lawyers and incident response consultants, yes. So if you do plan to pay up, be mindful of who you’re dealing with, as they may be considered a terrorist organization.

“Plausible deniability is meaningless in the context of an OFAC violation in strict liability,” said John Reed Stark, president of John Reed Stark Consulting, LLC, referring to the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. Last October, OFAC released an advisory warning companies not to make ransomware payments to groups on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN list) or have a “sanctions nexus.”

OFAC’s advisory outright states: “OFAC may impose civil penalties for sanctions violations based on strict liability, meaning that a person subject to U.S. jurisdiction may be held civilly liable even if it did not know or have reason to know it was engaging in a transaction with a person that is prohibited under sanctions laws and regulations administered by OFAC.”

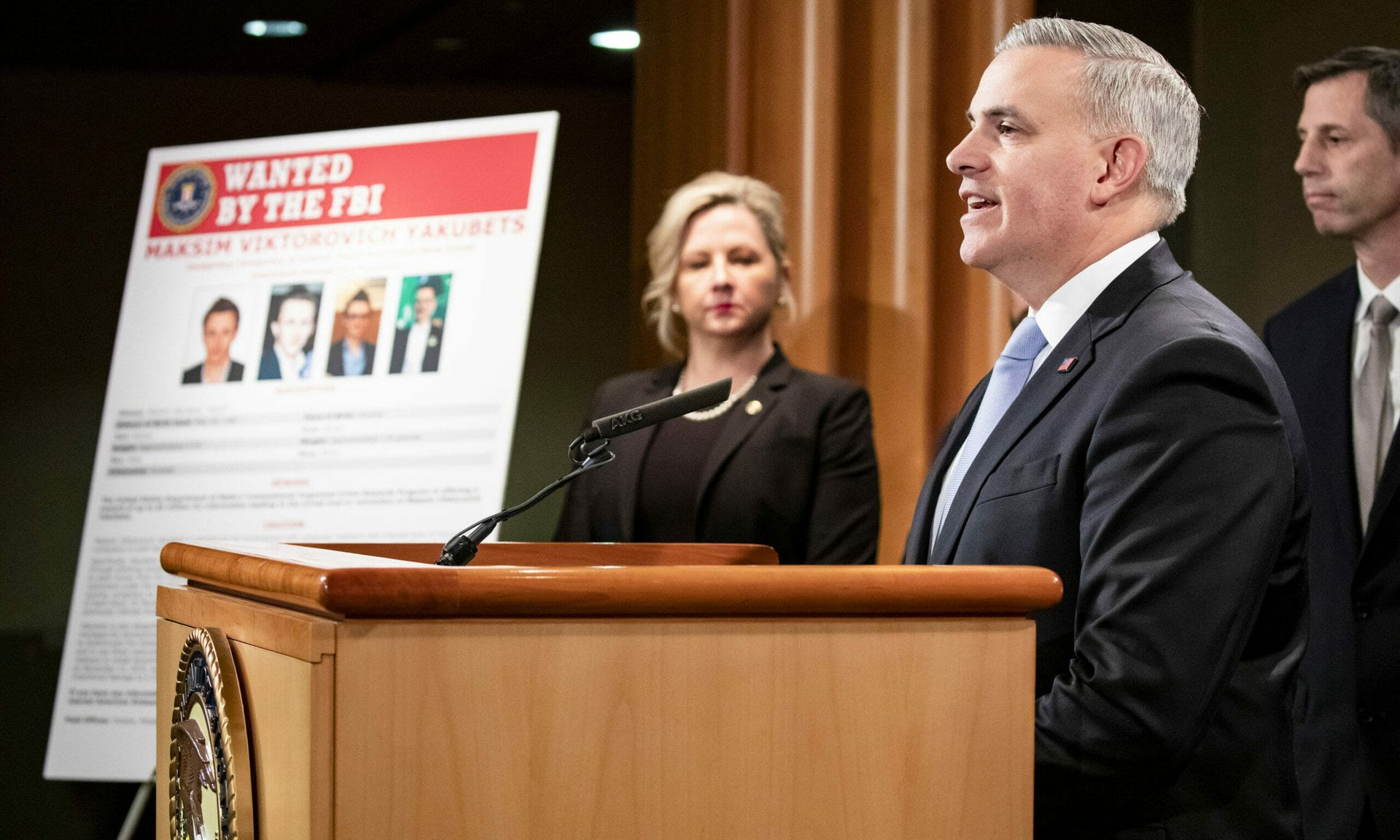

One such group to which this advisory applies is Evil Corp., a Russian cybercriminal group that has long been tied to financially motivated cyberattacks featuring the Zeus trojan, Dridex malware and WastedLocker ransomware. (In one prominent case, tech manufacturer Garmin last year was reportedly subjected to scrutiny after using a third party to facilitate a ransomware payment to Evil Corp., despite federal restrictions.)

Evil Corp. has also been tied to the newly emergent Grief, another ransomware that in recent weeks attacked the Lancaster Independent School District in Texas, the Vicksburg Warren School District in Mississippi and the Clover Park School District near Tacoma, Washington.

“Seems Grief is the latest sanction-evading (or plausible-deniability-providing) #ransomware product from Evil Corp #OFAC,” wrote Brett Callow, threat analyst at Emsisoft, in a June 15 tweet.

But as Stark said, there really is no plausible deniability when it comes to illegally paying sanctioned entities. “It doesn't matter how much due diligence you did. It doesn't matter if the president himself told you that this was not a terrorist. That would not operate as a defense in terms of an OFAC violation. It’s a strict liability statute,” he said.

It’s also not necessary for OFAC to publicly attribute a particular ransomware to a sanctioned group in order for a violation to become official, Stark added. So, if Grief ransomware is indeed an Evil Corp. operation and a victim of this encryptor program paid up, it would have been in defiance of OFAC regulations. With that said, however, it does make a difference how closely connected a group is to a particular ransomware.

"It is important to distinguish between an offshoot, subsidiary, or other type of relation between a sanctioned persons and another entity," said Matthew Tuchband, counsel at Arent Fox. "OFAC’s blocking prohibitions apply to transactions with the entities it places on its SDN and Blocked Persons List and any entities that are directly or indirectly owned 50% or more, whether individually or in the aggregate, by one or more other blocked persons. An offshoot of a blocked entity may or may not be 50% owned, and so it may or may not itself be off limits."

If companies aren’t confident as to whether or not they are dealing with a sanctioned group, there are at least certain mitigating actions they can take that could moderate any future actions taken by OFAC, should it turn out the actors are banned.

“The number one thing that you would need to do according to the October 2020 OFAC guidance would be to contact law enforcement and work with them,” said Stark. “OFAC looks at that as a very powerful mitigation.” To be clear, however, it’s not an absolute safe harbor. “The head of [OFAC] enforcement told me that himself,” he continued.

“As most sanctions regimes operate on the basis of strict liability, companies look carefully at the separate question of enforcement risk and the aggravating and mitigating factors that OFAC would consider in any enforcement response,” acknowledged Andrew Shoyer, a partner at Sidley who co-leads the law firm’s Global Arbitration, Trade and Advocacy practice.

As noted by Shoyer, the OFAC advisory states that “the sanctions compliance programs of companies should account for the risk that a ransomware payment may involve an SDN or blocked person, or a comprehensively embargoed jurisdiction.” However, “under OFAC’s Enforcement Guidelines, OFAC will also consider a company’s self-initiated, timely, and complete report of a ransomware attack to law enforcement to be a significant mitigating factor in determining an appropriate enforcement outcome if the situation is later determined to have a sanctions nexus.”

Additionally, “OFAC will also consider a company’s full and timely cooperation with law enforcement both during and after a ransomware attack to be a significant mitigating factor when evaluating a possible enforcement outcome,” the advisory continues.

In addition to coordinating with law enforcement, it’s also highly advisable to work with a professional ransomware response team that can help your business navigate these uncertain, choppy waters. This includes legal and digital forensics experts, and a payment facilitator.

"Advising ransomware victims is a case-by-case determination that depends on all of the facts and evidence present," said Tuchband, "and ultimately it is often a business decision that the ransomware victim needs to make in the context of excruciating timelines, risk of significant loss of business, sometimes risks to safety or even loss of life, and usually highly imperfect information about the ransom actor."

“One of my 12 steps of due diligence is to rigorously use and review the OFAC list of terrorists. And if you go to that database, you actually need to engage an expert to use that database effectively,” said Stark. “There are a few bugs to it. There are some bells and whistles to its search engine and you really have to have assistance” – especially to ensure that you didn’t overlook any potential connections between the ransomware actor that attacked you and a sanctioned group.

Stark’s complete list of mitigating circumstances can be found on his consulting firm’s website.

And if it seems decidedly inconvenient and confusing that a cybercriminal group on the federal “watch list” goes by multiple names and ransomware brands, know this: it’s a deliberate tactic specifically designed to circumvent sanctions. Case in point: Evil Corp. has also reportedly used another ransomware under the pseudonym of Hades to infect its victims without revealing any obvious connections to its true identity.

In a blog post, Crowdstrike said that Hades was the “latest attempt” by Evil Corp. “to distance themselves from known tooling to aid them in bypassing the sanctions imposed upon them,” after sanctions and DOJ indictments “ significantly impacted the group and have made it difficult for [them] to successfully monetize their criminal endeavors.” Evil Corp. has also been tied to the DopplePaymer, Phoenix and PayloadBin ransomwares.

The strategy can be effective because attribution is rarely easy. In particular, said Stark, “it becomes very difficult to pinpoint attribution with respect to any of the entities that that utilize ransomware-as-a-service where you're essentially franchising out various ransomware techniques and modus operandi. And I think it becomes very challenging for the government to make those attribution determinations… and then make sure no iterations of that attribution sprout up elsewhere.”

Still, Tuchband isn't entirely sure how effective such a strategy is. "Given that it is often hard to know who the ransom actors are in the first place, I am not sure how much they need to hide behind new offshoots," he said. "Right now at least, it seems that the number of common ransomware actors is small enough that OFAC identification of them could be effective, at least in the short term."