Researchers at Cisco Talos said they were able to fool biometrics-based user authentication technology on eight mobile devices by using 3D-printed molds to create replicates of users' fingerprints.

The process Talos researchers developed to fabricate a user's biometric signature required a painstaking effort, and in real life would require either direct or indirect access to a potential victim's fingerprints. For those reasons, this technique is not something that would likely be used by cybercriminals on a large scale to unlock people's devices.

However, in a blog post today, Talos argues that a persistent or tenacious adversary could potentially use this technique to compromise a device belonging to a highly targeted individual.

Talos says its fake fingerprints successfully bypassed biometrics sensors roughly 80 percent of the time in tests. "[T]his level of success rate means that we have a very high probability of unlocking any of the tested devices before it falls back into the pin unlocking," states the report, authored by Paul Rascagneres and Vitor Ventura. "The results show fingerprints are good enough to protect the average person's privacy if they lose their phone. However, a person that is likely to be targeted by a well-funded and motivated actor should not use fingerprint authentication."

For its experiment, Talos used three different methods of stealing users' fingerprints: via direct collection, as if lifting them from an incapacitated person; via a fingerprint sensor, like those used by border security or private security companies; or via a photograph of an object touched by the subject, such as a glass or bottle.

After collecting the fingerprint images, the researchers used a 3-D printer to create a mold, from which they created fake fingerprints out of textile glue. They also tried creating the fake fingers with the 3-D printer itself, but the end result was too "fragile, non-conductive and were too rigid" to work properly. Different resins may have resolved this problem, however, the report notes.

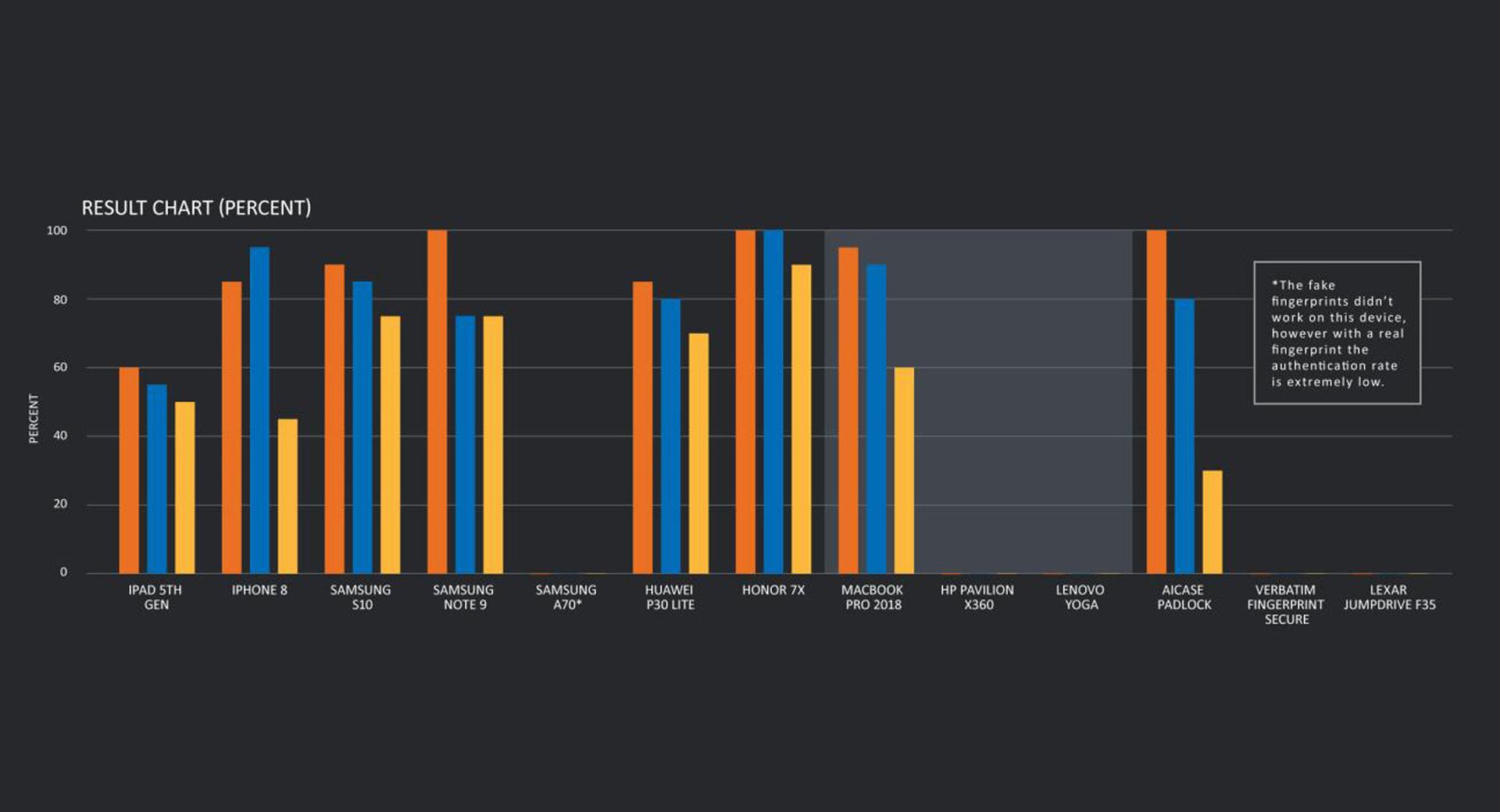

The collection methods had their limitations that required some trial and error, but ultimately the researchers achieved various levels of success fooling the sensors on a 5th generation iPad, an iPhone 8, a Samsung S10, a Samsung Note9, a Huawei P30 Lite, an Honor 7X (also from Huawei), a MacBook Pro 2018 and the AICase Padlock smart lock.

Depending on the device, direct fingerprint collection worked anywhere from 60 percent to 100 percent of the time, sensor-based collection worked from 55 percent to 100 percent of the time, and object-based collection anywhere from 30 to 90 percent of the time. (See the chart below.) Percentages are based on 20 attempts per device after identifying the best available fake fingerprint sample.

Talos was unable to trick the fingerprint comparison algorithms on Windows devices, the Samsung A70 (although the authentication rate even on real fingerprints with this phone is "extremely low," Talos reports), the HP Pavilion X360, and two USB-encrypted pen drives -- the Verbatim Fingerprint Secure and the Lexar JumpDrive F35.

Because the researchers' process required trying out multiple fake prints until finding one that consistently worked, Talos recommends that manufacturers limit the number of attempts at unlocking a phone in order to prevent this kind of exploit.

"For example, Apple limits users to five attempts before asking for the PIN on the device. The number of attempts was quickly reached during our tests," the report states. "Samsung implemented the same mitigation but the users must wait 30 seconds after five failed attempts and we can do that 10 times, making the final number of attempts 50, which is too high for proper security. We tested the fingerprint scanner on the Honor device more than 70 times so we assume you could do this an unlimited number of times. We have the same behaviour on the tested padlock where we do not reach any attempts limit."