The Supreme Court on Monday heard oral arguments in Van Buren v. United States, a computer crimes case whose verdict could significantly broaden or narrow the scope of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), including whether members of the ethical hacking community could face federal penalties.

The high court’s future ruling may ultimately hinge on whether the justices agree with the U.S.’s interpretation of the statute – particularly how it defines when a person has criminally exceeded authorized access to a computer system, website or app. In that regard, several justices on both sides of the ideological spectrum expressed doubt or confusion regarding the federal government’s stance.

The case centers around the conviction of Nathan Van Buren, a police officer in Georgia who, in exchange for a bribe, used his access to a law enforcement database to look up license plate information for an acquaintance. Although Van Buren was authorized to access the database, he was charged with computer fraud under CFAA because his actions were outside the purview of his job.

Cybersecurity experts and digital rights organizations claim the statute, passed in 1986, is outdated, and fear that bug hunters and pen testers could be charged if their research into systems are deemed excessive, even if they actions are intended to be ethical.

“These laws weren't even written with the concept of a good faith hacker in mind. That didn't really exist at that point in time,” said Casey Ellis, chief technology officer, founder and chairman of Bugcrowd. Ellis said that creating law that specifies what actions on a computer system are illegal is “inherently ambiguous… as computer systems get more complicated, so the idea of broadening things out to accommodate all of that ends up in this position where a whole bunch of things end up being a crime that shouldn't be.”

Jeffrey Fisher, the attorney who is appealing the 11th Circuit of Appeals’ decision to uphold Van Buren’s conviction, argued before the court that even employees and consumers could conceivably be prosecuted for disregarding written or verbal instructions for how to interact with a particular website or computer system.

In his opening argument, Fisher said that the U.S. government’s interpretation of the CFAA “would brand most American criminals on a daily basis,” including employees who might use their corporate laptops for personal business against their employer’s instructions. He said the law’s wording must not be viewed in such a way as to “transform the CFAA into a sweeping police mandate.”

Neither Fisher nor any of the justices specifically cited the law's potential impact on cybersecurity researchers or vulnerability disclosure programs, but Fisher did warn of the CFAA’s potential chilling effect – one that could certainly apply to cyber researchers: “The language of this statute has its own deterrent effect... For people who use the internet every day, they have to be aware of the criminal law," said Fisher. "And remember: this status has a civil component."

Opposing counsel Eric Feigin, assistant to the U.S. solicitor general, suggested Fisher was imagining worst-case scenarios in which prosecutors applied and enforced the CFAA far too broadly. “He’s trotting out this parade of horribles and telling you the only way to avoid it is to interpret [the act’s] language – which I think is quite clear – in his manner, as a way that would get rid of all of the privacy protection that the statute provides,” he said.

However, some justices seemed dubious of Feigin’s claim that the CFAA’s language implicitly imposes limitations that would preclude criminal or civil charges in many other cases.

So much rides on definition of "so"

The CFAA defines “exceeds authorized access” as “to access a computer with authorization and to use such access to obtain or alter information in the computer that the accesser is not entitled so to obtain or alter.” Fisher asserted that this means it’s illegal for authorized system users to obtain or alter data only if they are never entitled to said data. But the U.S. argues that the inclusion of the word “so” in that sentence means that persons are committing computer fraud even if they are accessing data they are normally entitled to, but are doing so outside of their stated terms of usage.

Dawn Mertineit, a partner in the law firm Seyfarth Shaw who practices in the firm’s Trade Secrets, Computer Fraud and Non-Competes group, called the government’s explanation of the word “so” as “muddled and somewhat tortured,” adding that the U.S. would “likely have an uphill battle convincing the court that the [current language supports] the broad interpretation of ‘exceeds authorized access.’”

“You would concede, wouldn’t you, that if the word ‘so’ wasn’t there, you would lose this case?” asked Justice Elena Kagan to Feign.

“I think it would be a much tougher case for us without the word ‘so’ your honor,” he replied.

Attempting to quell fears of prosecutorial overreach, Feigin also contended that CFAA’s “exceeds authorized access” language doesn’t apply to people who violate websites’ terms of services by, for example, registering themselves with false personal information.

A public website “is not a system that requires authorization,” said Feigin. “It’s not one that uses required credentials that reflect some specific, individualized consideration.” Also, he added, “services like Facebook and Hotmail that will give accounts to anybody who have a pulse – and even people who don’t because they don’t really check – thoses aren’t authorization-based systems, and I think that narrow meaning makes a great deal of sense in this statute.”

“What Congress was aiming at” when referring to authorization, Feigin posited, “was people who were specifically trusted. People akin to employees – the kind of person that has actually been specifically considered and individually authorized.”

If the U.S.’s suggested definition of “authorization” is indeed akin to employment, then a vulnerability researcher or bug hunter working under contract or as part of a bug bounty program could theoretically be accused of exceeding authorized access if his or her work was to be deemed out of bounds.

Justice Stephen Breyer also asked Feigin whether employees who are issued corporate-provisioned work computers are considered individually authorized. Feigin acknowledged that they are, but argued that they would nevertheless be protected from CFAA charges by the additional narrowing term “use such access.” Feigin said the act’s language implies that authorized individuals are only in violation of the act if they demonstrably abuse their privileged access to obtain or alter data that would otherwise be difficult to access.

“So if you decide to [use your work computer to] send an e-mail to your friend about when you're going to have lunch together, and that's something you could do from your phone, there's nothing special about using the access” that warrants charges, even though you may have technically violated company policy, he said.

But some justices expressed skepticism of Feigin’s implied definitions. “My problem is that you are giving definitions that narrow the statute that the statute doesn’t have,” said Sotomayor. “You’re asking us to write definitions to narrow what could otherwise be viewed as a very broad statute, and dangerously vague.”

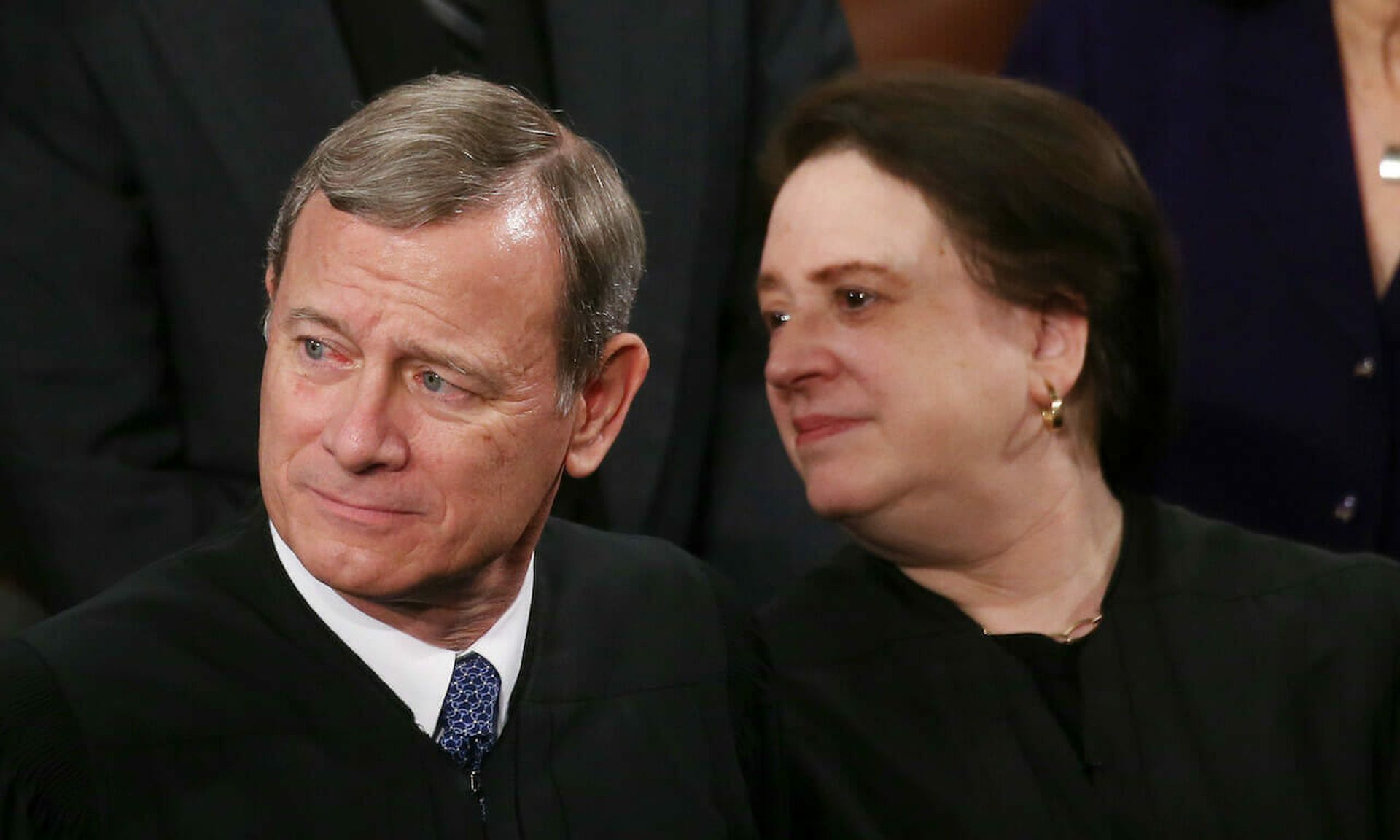

Additionally, Chief Justice John Roberts told Feigin, “I don’t understand your focus on authorization as a limiting term.” And Justice Amy Coney Barrett told Feigin that he was “attributing an awful lot of specificity to authorization that it doesn’t have.”

Barrett did however, also question Fisher’s interpretation of authorization, questioning why authorization should be looked at simply as a black-and-white “on-off switch,” using the metaphor of a babysitter who was given keys to the parents’ car “but uses the car to run personal errands.”

“Doesn’t the idea of entitlement or authorization itself have a scope component?” she asked Fisher, who in turn replied that in this particular statute, scope or purpose was not carved out by Congress.

A case of federal overreach?

Several justices also expressed concerns over the potential privacy ramifications of authorized individuals obtaining data outside the scope of the normal jobs, as Van Buren did. Justice Clarence Thomas, for instance, asked about a car rental company employee who uses GPS data not to locate a missing car but to stalk a spouse, while Justice Samuel Alito envisioned a scenario in which a bank’s fraud department employee sold credit card numbers for profit.

“Do you think that none of that was of concern when Congress enacted this statute?” asked Alito.

“I do not think it was,” said Fisher. “What Congress was concerned about was computer hacking, and that's up and down the legislative history – this new problem [in 1986] of computer of hacking.” Fisher acknowledged that Congress may wish to further amend the CFAA to specifically address Thomas’s and Alito’s examples, but under the law’s current language, there's no way to criminalize such malicious actions without also criminalizing “every other ordinary employee who violates an employee handbook.”

Fisher also said such actions typically already constitute crimes that can be prosecuted under other federal and state laws – just not CFAA.

Indeed, Justice Neil Gorsuch said regarding the U.S. government's “reverse parade of horribles” in which many computer crimes could potentially go unpunished, “I'm struggling to imagine how long that parade would be given the abundance of criminal laws available” outside of the CFAA.

However, Mark Krotoski, co-head of the Privacy and Cybersecurity Practice at Morgan Lewis and former federal cybercrime prosecutor, told SC Media he is less convinced that there are surefire alternative laws under which to prosecute acts such as Van Buren’s. For instance, he said, the Economic Espionage Act “only applies to trade secrets” and mail and wire fraud statutes “require a fraud scheme, which does not always apply.”

“Given the straightforward facts in Van Buren, where the sergeant admitted that it was wrong to use the law enforcement data base to run a search for money, if the Supreme Court reverses the trial conviction, there will be a gap under the primary federal computer statute to remedy this type of conduct by employees and other insiders given access to the network,” opined Krotoski, adding that this gap could even extend to “other statutes that often do not apply or are an imperfect fit to the facts.”

Regardless, Gorsuch reserved sharp criticism for the government’s invoking of CFAA in the Van Buren case, noting a “long line of cases in recent years where the government has consistently sought to expand criminal jurisdictional in pretty significant contestable ways that this court has rejected.”

“And I’m just kind of curious why we’re back here again on a rather small state crime that is prosecutable under state law and perhaps under other federal laws,” Gorsuch continued, adding that the CFAA’s language could be “making a federal criminal of us all.”

“I would have thought that the solicitor general’s office isn’t just a rubber stamp from the U.S. attorney’s offices and that there would be some careful thought given as to whether this is really an appropriate reading of these statutes,” Gorsuch stated.

Feigin held firm, however, insisting that the U.S. will not be prosecuting an endless number of cases under this statute. He accused Fisher of creating an “imaginary avalanche of hypothetical prosecutions” while being unable to cite legitimate examples of past CFAA prosecutorial overreaches.

But citing Marinello v United States, Fisher reminded the court that “you can’t construe a statute simply on the assumption that the government will use it responsibly” in the future.

Ellis from Bugcrowd said that government’s logic “assumes that everyone's operating in good faith, and has alignment around intent in the case of security research that's being done in the interests of making a system safer for users, but that involves passing information to an organization that might not necessarily want to hear it or might even have a history of responding negatively to that type of thing.” In reality said Ellis, CFAA has at times been used as a deterrent by software developers and other companies to deter research that might expose vulnerabilities.

Andy Baer, technology, privacy and data security chair at the law firm Cozen O’Connor, agreed, noting that the CFAA “in recent years has evolved into a weapon which website operators wield against data scrapers who crawl their sites in violation of the terms of use and companies use against employees who access corporate computer systems to obtain confidential information to take with them to competitors.”

Asked by Gorsuch if he was basing his arguments on any constitutional grounds, Fisher referenced violation of the fair notice doctrine due to the law’s “impossible vagueness” and ambiguity in terms of what actions are conceivably punishable. For this reason, Fisher argued that the court should lean on the rule of lenity, which requires the court, when a criminal law is deemed ambiguous, to rule in a manner that is most favorable to the defendant while still honoring legislative intent.

Legislative history also played a key role in the arguments, as several justices noted that the CFAA was introduced as an amendment to an earlier law that had originally included language explicitly making it a crime to use one’s authorized computer access for unintended purposes.

However, Fisher noted that this particular provision applied only to federal employees at the time, and when Congress later “expanded the statute eventually to cover all computers, basically, in the United States, it also did, at the same time, remove that murky ground of liability" by removing such language "because it was not… the core of the statutory problem.”

Feigin argued that CFAA’s history should be taken under consideration when interpreting the current law, and insisted that the illegality of improper use is still implied by the statute. But Fisher said it was “very dangerous to rely on legislative history to resolve ambiguity," noting that the wording was removed for a reason.

The justices in this case were also informed by a number of amicus briefs, including one from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Center for Democracy & Technology, Bugcrowd, Rapid7, Scythe, Tenable and a consortium of computer security researchers, who collectively emphasized the critical nature of vulnerability research and disclosure. The brief urged the court “to adopt a narrow construction of the law consistent with Congress’s intent and to clarify that contravening written prohibitions on means of access is not a violation of the CFAA.”

Conversely, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and 15 technical experts filed their own brief arguing that Van Buren’s actions constituted a significant invasion of privacy – exactly what the CFAA is meant to protect against. “The CFAA protects sensitive personal data and should be interpreted consistent with that purpose,” the brief states. “We need the CFAA, now more than ever, to be an extra check against abuse by the people entrusted to access sensitive data and systems.”

“I find this a very difficult case to decide based on the briefs that we’ve received,” admitted Alito, acknowledging both “concerns about the effect on… personal privacy of adopting Mr. Fisher’s recommended interpretation” as well as fears that adopting the United States’s CFAA interpretation would "criminalize all sorts of activity that people regard as largely innocuous.”

The Supreme Court has until June 2021 to issue a verdict on the case.